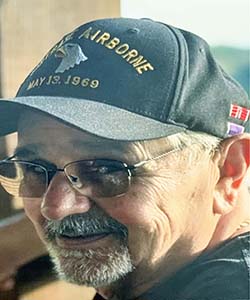

Army Vietnam War Flight date: 06/18/25

By Lauren Jones, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Jim Miller’s journey is a testament to resilience and the unexpected turns life can take. From the apprehension of being drafted to facing intense combat and a life-altering injury, Jim’s story highlights the profound impact of the Vietnam War and the enduring bonds forged along the way.

Jim knew he would be drafted after high school. He wasn’t planning to attend college and the war was escalating. “I got the ‘old greetings’ telling me to show up on April Fool’s Day,” he recalls about his order for induction into the military. So, on April 1, 1968, Jim’s brother drove him and a friend from their Mount Greenwood neighborhood to the induction center. They stopped at a restaurant on the way, but Jim was too nervous to eat. Although his brother offered him insight from his time in the Reserves, Jim still recalls feeling anxious, not knowing what to expect.

Upon arrival, they were put into two lines, as the military was drafting for both the Army and the Marines simultaneously. Military personnel walked down the lines, handing out slips of paper. Jim watched as every other person received a slip for the Marines. He was in line to receive one, but the person next to him, a guy from his high school who was about two years older and over six feet tall, was given the slip instead. “He never let me live that one down,” Jim laughs. “But it didn’t make any difference to me at that time.”

He was drafted into the Army and took the oath in downtown Chicago. He was bused to O’Hare Airport and flown to Fort Polk, Louisiana. This was Jim’s first time on a plane; he was 20 years old at the time. They arrived late that night, and that’s when the harsh reality of military life began. Jim recalled, “They started treating you like garbage right away.” After eight weeks of basic training at Fort Polk, which he describes as a “swamp and hell hole,” he was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for Advanced Infantry Training. It all moved along pretty quickly, Jim explained, “We didn’t graduate from basic training before moving on to the next post.” He believes they were rushed out because the next class was scheduled to start that Monday and the military needed to move things along. “We got our papers, but normally there’s a ceremony and parade, and we didn’t get any of that. We didn’t know what was going on, and our instructors, many of whom had served in Vietnam, just constantly told us, “This is how it’s going to be.”

At Fort Sill, Jim went into Fire Direction Control, which involved eight weeks of intensive math courses, including algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. They learned logarithms and used a slide rule to determine the distance, elevation, and direction for firing artillery. “You plot on a board where every military unit is at all times. Their exact positions. We had to know exactly where they’re at at all times.” These calculations were crucial for fire missions, which Jim emphasizes had to be ready to go quickly, often within 10 minutes.

During the War

Jim was first assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, B Battery, 2nd Battalion, 319th Artillery, working in the Fire Direction Center (FDC) and later to the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry as a Forward Observer (FO). During this time, he also learned how to be a Radio Telephone Operator (RTO). As an RTO, Jim would accompany the infantry, carrying the radio for a Lieutenant or Sergeant who would make calls to the batteries. Infantry lieutenants could not direct artillery, only mortars, unless a FO was unavailable.

When Jim was the FO, he would be out in the jungle, “walking the bush.” He recalls instances where infantry guys, not wanting to enter a village without knowing if it was safe, would have him call in a fire mission. They would pretend to be under contact by firing their M16s into the ground so that Jim could request artillery fire. The artillery would then shoot rounds to destroy areas or scout for enemy presence. They would intentionally fire a round 50 yards away from the target, allowing Jim to adjust the next rounds closer. He explained that many infantry officers were not “map savvy” and relied on the artillery FDC personnel. Jim felt a great sense of responsibility. He could also call in gunships using his call sign if they were under contact, directing them to targets.

As part of the FDC, Jim would often be stationed in metal cargo containers, called cans, that were placed together to utilize the space for plotting military locations on tables and maps inside. “They would call in and give us the longitude and latitude positions about every hour or so, and we would chart that on a map,” he explains. “If they called in a fire mission, we had to be ready to go.”

Hamburger Hill

In late April 1969, Jim had under 100 days left in his tour. He no longer wanted to be out in the field as a FO, preferring a safer assignment. He was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, C Battery, 2nd Battalion, 319th Artillery. Unfortunately for Jim, his next mission would be anything but safe.

About a month later, they were sent to the A Shau Valley, when the Battle of Hamburger Hill began. The hill was originally called Hill 937 and later nicknamed “Hamburger Hill” due to the heavy casualties and friendly fire incidents. The battle was part of a major operation into the A Shau Valley, which could only be entered during certain months due to monsoons.

Jim’s unit, C Battery, was on Firebase Airborne, providing fire support for the infantry on Hamburger Hill. He recalls that the enemy was deeply entrenched in tunnels, which made the fighting incredibly difficult. Jim explained the chaos of the battle, where gunships and bombers sometimes mistakenly hit American troops, making it a “meat grinder.”

On May 13, 1969, Jim was wounded during a sapper attack on Firebase Airborne. Sappers crawled up the hill undetected, wearing minimal clothing, carrying satchel charges and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). “They crawled up our hill. All they’re wearing is a little wrap around their waist. No other clothes on. That was the VC, and we didn’t hear anything,” he recalls. Despite the presence of infantry and Claymore mines on the perimeter, the sappers successfully infiltrated the base. Many artillerymen were sleeping in their bunkers and were killed when satchel charges were thrown in.

Jim was sleeping at around 3:15 AM when the attack began. Initially, he and his buddy thought it was just harassment rounds, which were common. “They knew we were up there getting situated since we were brand new to the area. And we fired harassment rounds, too. We called them Dr. Pepper because we’d fire at 10, 2, and 4, which were the numbers on the bottle at that time,” Jim explains. However, when they heard M16s and other weapons firing, they knew it was more serious.

Between the infantry and artillery guys, around 30 men were killed and 60 wounded from his unit that night. Jim worked 8 hours on and 8 hours off, and the attack just so happened to be during a break for Jim. Otherwise, he would have been with the men killed in the FDC cans. Right after he got out of his bunker, Jim was hit in the legs by an RPG. His boot was blown off, and he had large gashes and broken bones in both legs. Lieutenant J.D. Culwell and another guy carried him to a safer location. The Lieutenant, with whom Jim had a good relationship, instructed two new guys to protect Jim before he ran back to the field. “You guard him,” he demanded. “Don’t let anything happen to him. If something does, I’ll come back and get you.”

Around 40 years later, while running reunions and posting pictures online, Jim reconnected with Mike Delaney, one of the men who helped carry him the night he was injured. Jim never knew his name, but Mike clearly remembered the incident. “We met up at a reunion in Clarksville, Tennessee, near Fort Campbell, and he shared experiences that only someone who had been there would know,” Jim said, describing the reunion as “very emotional.”

Jim was taken to a MASH unit, then to a major hospital in the Phu Bai area in Vietnam. Within 13 hours of being wounded, he was on a flight to Japan, still in two full leg casts. At the 6th Army Hospital in Japan, he saw many severely injured soldiers, including a burn victim whose breathing caused bubbles to come through his burns. He also saw a friend from the Quad Cities who had lost a leg that night.

Jim called his parents from Japan to inform them of his injury. This ended up being crucial because another Jim Miller had been killed that same night, and his parents were served an official letter, mistakenly saying their son had been killed.

Lieutenant J.D. Culwell

During his time in Vietnam, Jim became close friends with Lieutenant J.D. Culwell, whom he initially met while with B battery. Culwell was an officer who would review their calculations in FDC, work the shifts with Jim, and even share the same bunker. Later, when Jim was at Firebase Airborne, Culwell joined his C battery because they needed more guns. Jim recalls being so happy to see him.

Years after the war, Jim connected with Culwell’s family, who confirmed that he had died by suicide. “That was a heartbreaker when I found that out,” Jim solemnly recalls. He was able to share pictures of Culwell with Culwell’s son, who had never seen photos from his dad’s time in Vietnam or heard stories about his heroic acts.

“I told him about his father,” Jim explains. “About how important he was. I told him what his dad did that night and throughout his time there. When we were getting overrun, he carried me to a safe spot and went back out on the phone, directing the ships coming in. He was walking around talking and right in harm’s way. “I don’t know and don’t care what he did after Vietnam. But during that time, he was a real hero.”

Veteran pride

Jim flew from Japan to the US and spent the next three months recovering at the Great Lakes naval base, learning to walk again. When his parents arrived, Jim recalls his dad immediately checking to see if he still had both legs, concerned he might have been downplaying his injury. Despite the intense recovery, Jim and other Vietnam veterans in the hospital had “a lot of fun,” racing their large, wooden wheelchairs down the corridors, much to the annoyance of the nurses. “But what were they gonna do to us?” he laughed.

Jim was put into temporary retirement from the military, which he later learned came with more benefits than a standard discharge. He and his wife have not paid for health insurance and receive free pharmacy benefits through his military retirement. They have also enjoyed discounts at military retirement areas, including numerous trips to Hawaii and Disney World with their family. He is a supporter of the Major Richard Star Act, which aims to provide both military and disability pay to veterans who have served for less than 20 years and have a combat-related disability.

Jim officially retired from the military on Nov. 12, 1969, reaching the rank of SPC/4 and receiving a Purple Heart for his injuries at Hamburger Hill. He also received the National Defense Service Medal, Army Commendation Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Expert Badge (Rifle M14), and the Bronze Star Medal with 1 Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster & “V” Device. In addition, he has a presidential citation awarded to his company and a “brave eagle coin” from the 101st Airborne, given only to “bravest men who have ever fought in battle,” which he considers special. He was presented with his Purple Heart and other medals at a parade at Fort Sheridan.

His return home was unlike that of many other veterans. Jim didn’t face backlash because he went straight to the hospital in Great Lakes. Once he arrived back home, people would ask about the injuries to his legs; he would tell them it was from a car accident to avoid having to discuss Vietnam. He kept his military experience to himself for a long time and, unfortunately, didn’t realize until much later that he had PTSD. His wife, Patricia, had observed it, and Jim had difficulty holding a job. Veteran groups helped him work through his issues, and he started seeking professional help for his mental health about 10 years ago. This has made a significant difference in his health, and Jim encourages others to seek help.

Jim still maintains contact with a core group of men from his Vietnam unit. They now travel together annually with their families, renting houses and taking turns cooking meals, which helps maintain a strong camaraderie.

Patricia and Jim met after he returned from his time in the military. They have three children: two boys and a daughter in the middle, and six grandchildren. The family has a close relationship, and Jim is hopeful one of his sons will have his REAL ID by the day of the honor flight so he can escort him.

Jim heard about Honor Flight Chicago through veteran groups. He has previously visited Washington, D.C., including for the dedication of the Three Servicemen Statue. While he is familiar with the area, he understands the significance for other veterans who have never been there and looks forward to sharing stories with them.

Thank you, Jim, for your dedication and service. We hope you enjoy your flight!