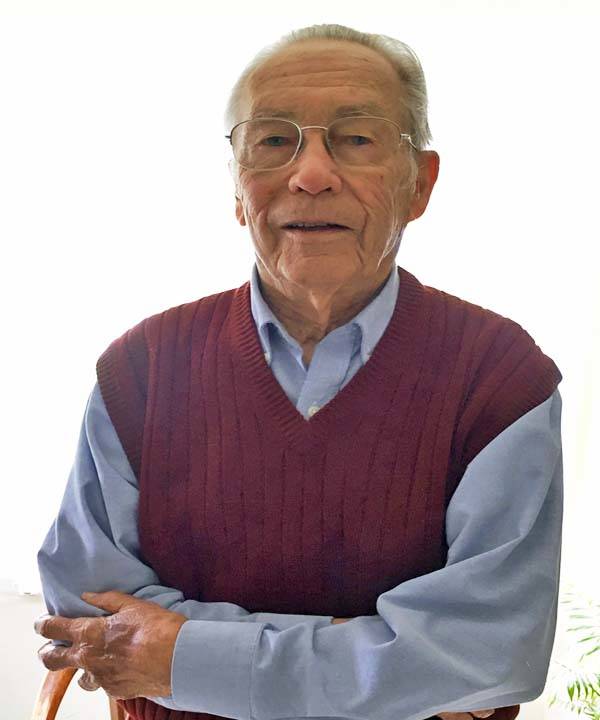

U.S. Army World War II Woodridge, IL Flight date: May, 2019

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Arthur Berg was born to Swedish parents on the south side of Chicago in 1923. His father was musically inclined and Art followed in his footsteps. He started playing the piano at age eight and began to play the clarinet a few years later. In high school, Art joined the ROTC, in part because they had a band that he wanted to join. His dad was the commander of the local American Legion post so Art was exposed to the military and veterans at an early age.

Art graduated from high school in 1941 and was drafted in 1942. He had his choice of which branch of service to join. His father encouraged him to join the Navy, in part because that’s the branch that he had been in. Art, though, didn’t like the water, and he also hoped that if he joined the Army he could be in a band. He enlisted in the Army and was sent to boot camp in early 1943. Shortly after he got to boot camp, he had to return home because his father had become very ill, and died shortly thereafter. Art was happy that his father had a chance to see him in his uniform before he passed away. When Art returned to boot camp after an absence of several weeks, many of the men he had been training with had been shipped out, so instead of being with those men in the 106th division, he ended up in the 78th division. Although he didn’t know it at the time, the repercussions of this change would be significant and may have even saved his life.

Art trained for three months as an infantryman, but when he heard that the division was establishing a band, he signed up to audition and was selected to be a member. For the rest of the time that the division spent in the United States, his primary role was as a musician. The 75 man band played in parades, troop reviews, rallies and concerts for both troops and local communities. The band also toured around the southeastern United States and performed in rallies that encouraged people to buy war bonds. Art was a full-time band member and also served as the instrument repairman, in part because of all the musical experience he had gained while growing up.

After a year and a half in the United States, in October 1944, the division shipped out, sailing from New Jersey to Plymouth, England. After a couple weeks there they boarded LST’s in Southampton and set sail for France, landing in Le Havre in November. One of the LST’s struck a mine as they were approaching the shore, and an MP was shot by a sniper shortly thereafter, so they quickly realized that even though the battle lines had moved beyond this sector, there was still plenty of danger. After having Thanksgiving dinner in France, the division boarded trains bound for Belgium. The trip lasted several days, and they were trapped in boxcars for most of it, with no heat or light and very little food. They had to take turns standing and sleeping because there wasn’t enough room for everybody to lie down at the same time. The band traveled as a group, even though their instruments had been shipped to Europe separately.

They eventually got off their train at the border of Belgium and Germany. Since the band wouldn’t be performing for the rest of the war, Art wasn’t sure what assignments he and the other musicians would receive. Since the band was part of the headquarters organization, they eventually all took roles in that group. In Art’s case, he was assigned to be a military policeman, and this is what he did for the rest of the war. His responsibilities included road patrolling and controlling, as well as guarding POW’s. Art generally enjoyed this work and was glad that he didn’t have to go to the front and become an infantryman. From his father, he had learned about authority and also about the military code of conduct and these traits helped him in his new role.

Even though Art was usually about a mile behind the front line, he was still in frequent danger. He recalls one night when on patrol he encountered a drunken GI who didn’t know the password. When Art confronted him the soldier stuck a gun in his stomach. Luckily Art was able to talk the soldier out of doing anything stupid. The headquarters group was also subject to frequent German strafing and artillery fire. He recalls that in one town there was a German reconnaissance plane that would drop flares every night at dusk. The soldiers nicknamed him “Bed Check Charlie.” The role of MP was made more difficult after the Battle of the Bulge. Germans had dropped English-speaking soldiers dressed as MP’s behind American lines. They disrupted communications and made U.S. soldiers leery of MP’s for the rest of the war.

Shortly after the 78th division got to the front, the Germans launched the Battle of the Bulge. This is where Art’s assignment in the 78th division instead of the 106th division came into play. The 78th division was stationed at the northern edge and was at the fringe of most of the fighting. The 106th, though, was directly attacked and overrun. Over 6,000 Americans in that division surrendered. Art often thinks about twists of fate like this—if his father hadn’t died when he did, then there’s a good chance that Art would have been killed or captured during the war.

It isn’t just the big battles that stick out in Art’s mind. He recalls that GI boots were never good at keeping your feet dry and while some people had overshoes, they weren’t that common. One day he got the idea to go to the graves registration unit to see if they had any extras from deceased soldiers. The sergeant said to help yourself—the dead soldiers don’t need them. In thinking back on it, he’s thankful for the pair of overshoes donated by a dead unknown soldier, but also questions the things that people will do in difficult situations to keep themselves alive that they wouldn’t think of doing otherwise.

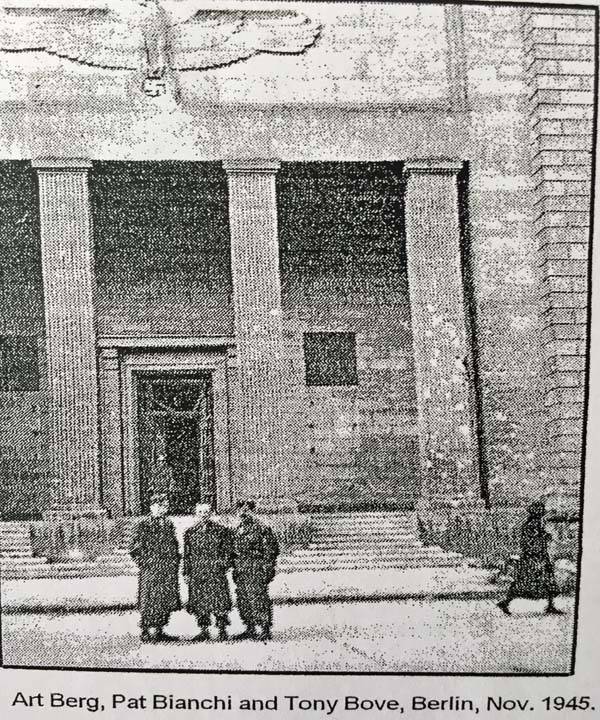

Art’s lasting memory of the day of the German surrender was that things were quiet for the first time since he arrived in Europe. There were no explosions and no gunfire. Shortly after the war ended, the band was able to retrieve their instruments from where they were stored in Belgium and began putting on parades and concerts for both troops and civilians. He says that the German civilians were amazed at how quickly the American military men had switched from war to peace. He stayed in Europe until January, 1946. Shortly before leaving, Art was transferred to the 84th division whose band played the music for General George Patton’s funeral. Art was honored to be a part of that ceremony. By the time he left the army, Art had achieved the rank of technical sergeant.

Art had always been interested in art, and upon returning home, he went to art school with the benefit of the GI bill. He originally wanted to be a cartoonist, but as time went on he realized that his talents were more suited to commercial art so he ended up attending Chicago Technical College, where he focused on architecture and engineering. He got a job with an engineering firm and then in 1960, he took a job at Montgomery Ward. With the role of project supervisor, he coordinated the construction of new retail stores. He retired from there in 1988 and performed consulting work on tax issues related to real estate for an additional nine years. Art and a group of about a dozen war buddies had periodic reunions after returning home, but over time those became less frequent. He has stayed involved in military affairs through the American Legion where he’s been active for 35 years.

One day in the early 1950’s, Art was at an ice skating rink and met a young lady named Carol. He knew right away that “this was it.” They wed in 1955 and have been married for 64 years. They have two sons, one of whom lives in Florida and the other in the Chicago area. Sadly, Carol, an artist, suffers from dementia and has had to move to a facility. However, Art relates that the walls of their home they had lived in since 1960, are covered in her artwork. Art says that even though she doesn’t live there anymore, he sees her every day in her artwork.