U.S. Army World War II Morton Grove, IL Flight date: 10/06/21

By Victor Maurer, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

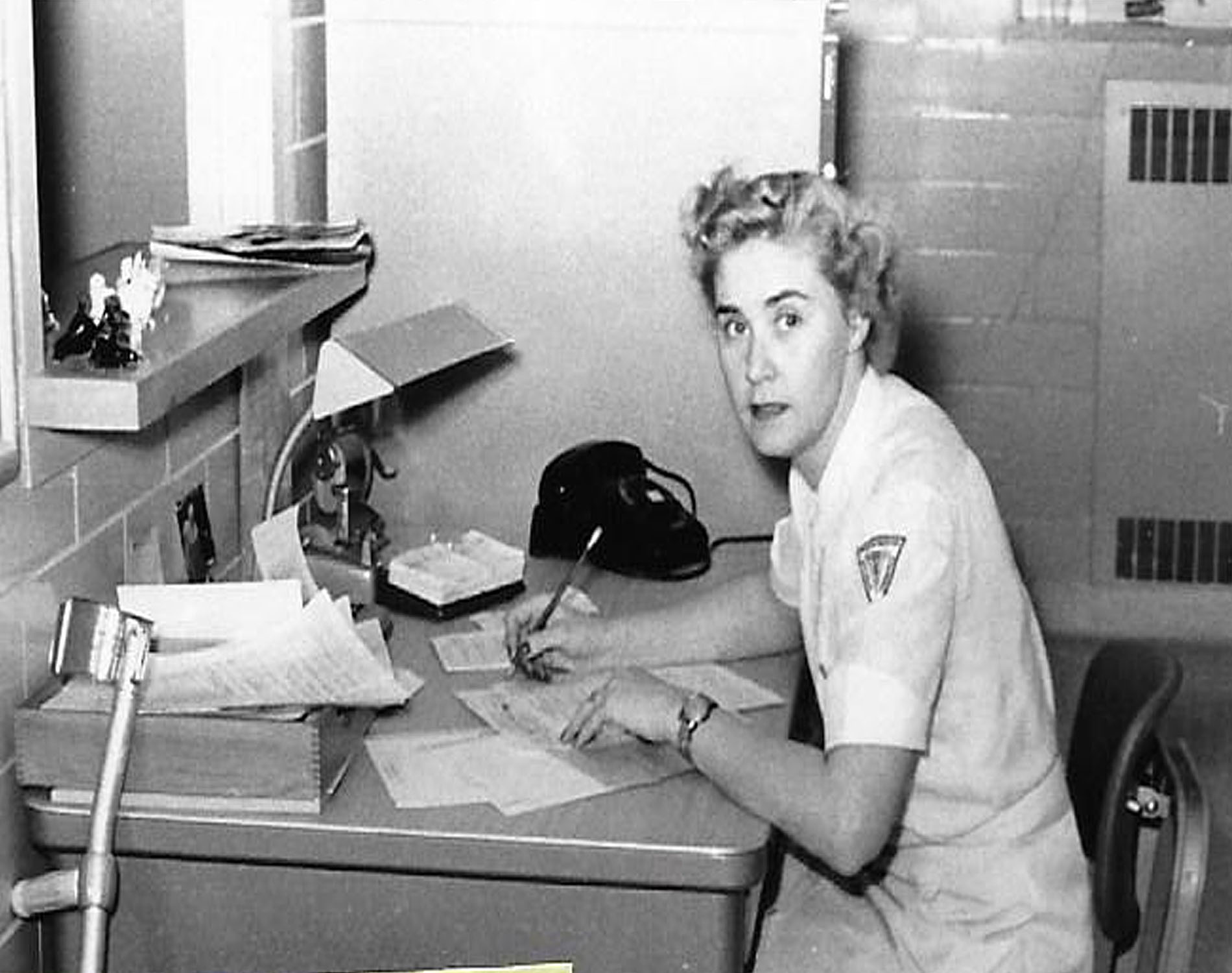

2nd Lieutenant Bette Horstman served as a physical therapist in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in the Pacific during World War II. This is her story.

Born in Hibbing, Minnesota in 1921, Bette Horstman grew up in Chicago, Illinois with her younger sister and parents. She is the daughter of an entrepreneur and Chicago business owner and a stay-at-home mother, who, as Horstman describes, was a “real lady.” She benefitted from a loving home, and a comfortable childhood, recalling that her family gave her many opportunities as a young girl to travel on vacation and engage in hobbies such as horseback riding. Their encouragement of her to pursue a college-level career after graduating from high school may be considered ahead of its time. Horstman graduated from the University of Michigan in 1943 and was soon accepted by the Mayo Clinic’s emergency physical therapy (PT) program – no small feat. The program was mostly women at that time, because as Horstman tells it, Mayo was concerned that men were too motivated by money to accept the wages then paid to physical therapists.

While at the Mayo Clinic, the school was visited by a U.S. army recruiter who told them about their country’s need for their skills and service. War is a horrific thing, and there was a great need for physical therapists who could care for men who were ill, ailing and injured in need of physical rehabilitation. Horstman, along with all but two of her classmates, answered the call to service and enlisted. Both of Horstman’s parents were troubled by her decision to enlist, though they did not stand in her way.

“It was wartime and I felt I was needed.”

Horstman had hoped that she would be able to stay in the United States, and would have preferred to join the Navy – but the need for her skills was greatest in the Army. She enlisted in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. She completed a bang-bang crash course training in formal instruction, before she was sent to Harmon General Hospital in Longview, Texas for her hands-on training. It was there that Hostman was first acquainted with the physical consequences that fighting the war had yielded returning soldiers.

After Harmon General Hospital, she was sent to complete basic training at Fort Lewis along with a cohort of other enlisted female medical personnel. Despite their intended positions being at a distance from any combat, the women were still trained as any other GI in the U.S. Army. They were taught how to handle different weapons, perform ground maneuvers, and were given the standard uniform, which included a large gas-mask and equally heavy boots. The trainees had no knowledge of where they might be sent, but by the time Horstman was shipped overseas, it was clear that her contribution to both the service and the profession of PT would leave a lasting impact.

In 1945, her first assignment as a newly commissioned 2nd lieutenant was treating prisoners of war at Tripler General Hospital in Oahu, Hawaii while she awaited her final placement. Horstman would eventually be sent over 3,700 miles further west to Saipan, which had seen heavy combat during the Battle of Saipan, Horstman arrived barely a month after the capture of the Island by U.S. forces. There was still active fighting. She would spend the majority of her Army service on the island. On Saipan, Horstman observed the ruins of bombed buildings paralleling the beautiful tropical flowers growing beside beaches. She learned of the term “Suicide Cliff” and witnessed B-29s taking off on mercy flights to Japan. She attended simple fractures, sprains, and aches from the resident civilian population and prisoners of war and treated burn patients from bombing runs gone wrong and infantrymen with self-inflicted wounds.

“You can’t get strong without resistance.”

Her investment in PT included responding to limited equipment with improvisation, as well as her proudest moment: training her fellow corpsmen in PT methods so they could assist her in carrying out patient exercises. In place of standard therapeutic cuff weights, she used gallon jugs filled with water or tomato cans from the mess. Without conventional resistance bands, Horstman opted for rubber strips cut from old tires. Otherwise, they worked manually to help their patients heal. Often, she would be asked to treat Japanese POWs, who she remembered as being unusually tall for Japanese, perhaps signifying that there were marines in the Imperial Army. She found it difficult at first to treat them, because of the language barrier, but would ask them to “tell me where it hurts” and learned to observe their body language to detect when a treatment was optimal and when it was too much. “They were starving,” she said. “And they didn’t know that the war was over.”

In her post-service life, following her discharge from the U.S. Army in 1946, Horstman helped establish the PT departments at three Chicago area hospitals. A long-time member of the American Physical Therapy Association, Horstman was also the first female in the state of Illinois to open up her own PT practice and she even went back to school to complete both a master’s in education and a nursing home administrator’s license. For her service during World War II, Horstman has received a Meritorious Service Unit Citation with 1 Star, the Asiatic-Pacific Service Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

“You have to give back.”

In supporting her own mental and physical health at the age of ninety-nine, Horstman’s life continues to be about giving back and staying active in many ways. In recent years, Horstman has worked with the Veterans of Foreign War, the American Legion and at the North Chicago VA as a post commander, where she has volunteered for nearly two decades. She first gave her time as a health educator and before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, she volunteered for the bedside care program “No Veteran Dies Alone.”

Now retired from PT, Horstman looks back on her years as a wartime physical therapist and maintains that her time in the Army taught her how to think outside the box. Horstman’s determination and the application of her military experience in civilian life contributed to a successful and meaningful career that left a lasting impact on Chicagoland healthcare. In her commitment to staying active and contributing to what she loves, Bette Horstman can still be found volunteering with her fellow veterans, or, as she did back in the days of her basic training, spending time at the nearest bowling alley.

Thank You Mrs. Horstman, for your service. Have a great day in DC.