U.S. Army Vietnam Villa Park, IL Flight date: June, 2019

By Jack and Ellen Walsh, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Maybe his family’s history of seeing atrocities is part of the reason Eddie Krupiczowicz loves America so much. Whatever the reason, he has spent a lot of his life in the service of his beloved country.

“I was born in 1945. My mom’s home was Gdansk, Poland, and as a teenager she watched the Nazis invade. Terrible things happened. She told me the hard story of when the Nazis put all the Jews in town into a bomb crater in the middle of town, and made all the other townspeople gather around and watch. The Nazis then poured gasoline all over the Jews and lit them on fire.”

Eventually, Nazis gathered up a lot of the young people, including Eddie’s mom, and took them in cattle cars to a concentration camp to work as slave labor in Germany. She became the camp baker, met a Sicilian man, and soon Eddie came along. About two weeks before he was born, his father tried to escape and was shot and killed. “I was born in the camp on March 30, 1945. The commandant took us for his farm, so she could do the cooking and cleaning for his family. We did okay, and the war ended in early May.

“I was fatherless, and mom and I went to a refugee camp in the French sector. My mom learned French, and became an interpreter. We were alone because her parents and uncles had all been killed in the camps. My mom met another Polish man. Eventually, when I was about 5, they got married and gave me two brothers. Finally, we were resettled on an egg farm in the American Sector.” The farm was near the small town of Ediger along the Moselle river in Germany. Their closest neighbor was a former German soldier, and neither he nor the rest of the town ever accepted them, the only Polish family in town. “They treated us like dirt. Quite often, I would get beat up on my way to or from school. Eventually, I learned I had to stand up and defend myself.”

“Finally, we had an opportunity to be relocated to the United States. We left right after Christmas, 1956. I remember the ship across the Atlantic, with terrible storms. We came into New York harbor, and I saw the Statue of Liberty – she was so beautiful! Originally, we were settled in the Bronx, but my dad knew we had friends and relatives located in Chicago, so soon we took the train here. I was about 11 or 12 at the time.”

Polish-American societies in New York and Chicago helped them get settled, and though none of the family spoke English — there were plenty of neighbors that spoke Polish! Their first Chicago home was in St. Hedwig’s Parish. “In elementary school, I had a very large paper route, and got up early every day to deliver papers. Over the years I learned English, and in 1965, I graduated from Holy Trinity High School on Division Street.”

In the summer of 1965, Eddie got a job at a gas station. Often, after work, he and his friends would hang around the station. “One night in July 1965, I was suddenly attacked from behind and beaten. It was my stepfather. Over the years, due to his heavy drinking, he had often gotten abusive with me. This night he was mad at me because I hadn’t come home right away.” For the next few nights, Eddie slept in a buddy’s car rather than go home.

“The next day, I went to an Army recruiter and told him I wanted to join up and get out of town as quick as possible. I said goodbye to my mom, and within a few days was on a train to Ft. Knox, Kentucky. I didn’t mind boot camp. They yelled at me, but I was used to that from home. I did really good in all my schools. In marksmanship, I shot Expert; in Advanced Infantry Training (AIT), I had no problem. Because I wanted to go Airborne, I went to Ft. Benning, Georgia, for jump school, then to Ft. Dix New Jersey for radio operators’ school. While there, I volunteered for helicopter pilot school, at Ft. Rucker, Alabama. However, my left eye is somewhat off and that knocked me out, so they recruited me to be a helicopter crew chief. I also had to learn how to shoot machine guns used by the door gunners. Someone had told me to get as many schools as I could, so I could be more valuable.

To continue his training, Eddie went to Ft. Belvoir, Virginia, for combat engineer school, working with explosives. He made the rank of E-4 there, and was able to apply for citizenship. “My sergeant drove me to Alexandria, Virginia, on a Monday, and on Friday I was sworn in. Even my commander was there for the ceremony. They asked me where I’d like to go. I didn’t want Vietnam, so I said Korea. I was sent to Camp Casey, Korea (about 40 miles north of Seoul), and served 18 months there.”

After Korea, he had 30 days leave at home and was scheduled to report to Ft. Dix. But one day there was a knock on the door, and a Lieutenant was there with new orders. He said, “Son, you’re going to a sunny country.” And off to Vietnam it was. He flew to Ft. Lewis, Washington. “But at check-in, they said ‘We can’t send you to Vietnam; that’s a combat zone and you’re not a citizen.’ I argued that I was. ‘All my friends and buddies are going, and I volunteered for it, I’m going.’ They wanted proof, so I called home, and had my Mom overnight express my naturalization papers to me.

“At Ft. Lewis, they familiarized us with the M16, took our Class A’s and gave us our jungle uniforms and boots, and put us on a ship to Hawaii. We had a little time to our self in Hawaii. A few of us got a little rambunctious, hit some bars — and missed the ship. Soon the MP’s found us and hauled us off to the stockade. We thought that we were not going on to Vietnam, but the MP’s said, ‘Nope, you’re going the fastest way.’ They put us on a Braniff flight direct into Saigon Airport.”

In Vietnam, soldiers were put onto busses, and then given a field class on all the different weapons and booby traps to watch for. About a week later, they were loaded on deuce and a half trucks, and given M-16s with an M-60 on the truck, along with a bunch of ammo. Eddie was sent up to join the Wolfhounds, 2nd Battalion, 27th Infantry Regiment at Cu Chi, about 30 miles NW of Saigon. “We got to Cu Chi, and finally go out on a night ambush. We set up the claymores and all of our weapons. Suddenly, we hear something and one of the new guys jumps up and yells ‘Halt! Who goes there!’ He’s the first one to get killed. We set off the claymore mines and the weapons. He was the only casualty. We make it back in, and the all the sergeants and CO came out yelling. ‘You don’t stand up and yell who goes there! That’s the fastest way to end up in a box. You get to go home, but not alive.’”

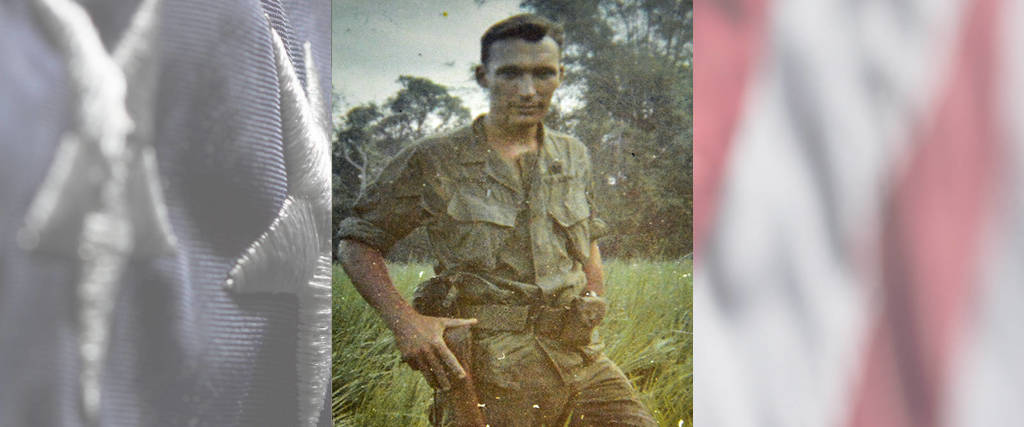

Eddie’s unit spent, on average, about a month in the field. Some of the guys didn’t bother shaving. He says he shaved every chance he got — but he did grow a handlebar mustache. “We were constantly on the move. We’d get flown in, or if it was close, we’d go in on trucks. We’d go to one spot, set up a temporary base camp, and it was either day patrol, night patrol, or ambush.

“After a while, the platoon sergeant said ‘I need a volunteer.’ Well, I was the shortest and skinniest guy, so it became me. I found out that I was going to be a tunnel rat. I didn’t know what to expect. They put a harness on me, with a big long rope. I had a Colt .45 pistol, a sawed-off Remington shotgun, extra shells, 4 white phosphorous grenades and a flashlight. One of the previous tunnel rats said, ‘Good luck. You may last a month or two, but then you’ll want out.’ They told me ‘just crawl in there, and keep real quiet, until I came up to a wall, then listen. If you hear voices, they’re not going to be in English. Take a grenade, very quietly remove the pin lever, count to 3 and pop it over the wall. Take another one and do the same thing.’ After that, all I heard was screaming, because that stuff was nasty.

“Then I would crawl over the wall and look for maps and other intelligence information. I did that for about a month-and-a-half, one or two a day. There was all kinds of booby traps, snakes, red ants, spiders – I started taking a long stick or cane, and I quietly would try to remove all that stuff.

“We had caught three VC’s and put them on a helicopter; I was sent as one of their guards. There also was a couple of soldiers from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). The prisoners were all tied up, and one of the ARVNs began to question one of them. He wouldn’t talk, so finally the ARVN picked him up and threw him out of the helicopter. He went to the next prisoner, and this guy started talking like crazy.

“In the village of Cu Chi, I met a Vietnamese-French girl named Rosie. She was a teacher, and her parents were college professors – her father French and her mother Vietnamese. Things got going, and finally I got permission to marry her. Then the Tet Offensive started, and I was assigned to the Tan Son Nhut Airport to protect it. After things settled down, we went back into the village.” Eddie discovered Rosie had been killed and found with a cardboard sign on her saying ‘American sympathizer.’ He recalls “her mother and father had been killed in an earlier war because they had sided with the French, and her brother had been killed because he had refused to join the Viet Cong. She was the last of her family.”

Eddie made sergeant and became squad leader. They were sent by helicopter into Cambodia with a few guys without insignia on their uniforms. “By morning those guys were all gone. We found out later that they were CIA.” Eddie was in Nam about 11-1/2 months, and was discharged in July, 1968.

“I got home on July 3, 1968, and it was a nightmare for me. People were throwing firecrackers and M80’s and stuff into the gangway by our basement apartment. The Democratic convention was in Chicago, with all the protests and riots. Since I didn’t have any civilian clothes, I had to wear my uniform until my mom and I went shopping. Once I changed into civilian clothes and got back in the neighborhood, I started to get better. I still had a cocky attitude, though. A few friends and I went downtown and let our feelings be known to a few of the protesters.”

“I had a hard time finding work, but I finally got a job at Ekco Corporation as a timekeeper, and dated around. After about a year, a guy in the neighborhood set me up with a girl on Valentine’s Day on a double date. In about a month, we got engaged and then married on July 25, 1969.”

In 1989, at age 44, Eddie decided to go back into the Army as part of his retirement plan. He re-enlisted in the Army Reserves, Custer Division, but they would only give him the rank of corporal. He opted for Drill Sergeant School in Fort McClellan, Alabama. “I’m in my forties taking all of those PT (physical training) tests!” He stayed in the Reserves as a Drill Instructor until age 62, and in 2007 earned his retirement!

Kathy and Eddie live in Villa Park and will be married 50 years in July. They have three sons and a daughter, and seven grandchildren. All three of their sons have served in the military, which included assignments with the Special Forces and Airborne. They are proud to have raised a patriotic family.