Marines Vietnam War Coal City, IL Flight date: 05/14/25

Surprisingly, James Phillips didn’t get the nickname “Hop” in the service, as many do. He’s had it since childhood. Growing up on a farm in Mazon, Illinois, where they had ponies, his favorite TV show was Hopalong Cassidy. Because his grandfather and father were also named James, his father started calling him Hopalong to help avoid confusion among family members. It eventually shortened to Hop.

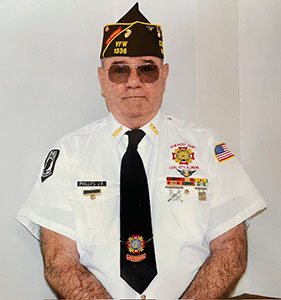

He has a big, easy grin that bursts from a positive and cheerful attitude, and he never runs out of humor to make you laugh and smile right along with him. Always ready to give of his time and talents, he currently serves as Commander of the VFW St. Juvin Post 1336, and presents the history of the American flag to local elementary students with his Honor Flight Chicago buddy and fellow (Army) veteran Keith Roseland.

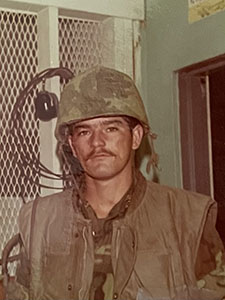

Don’t let that joyful demeanor fool you into thinking he’s easy-going, though. Ambition has been the name of his game since he joined the Marines in 1968. He moved up from Private First Class to Lance Corporal to Corporal to Sergeant in a span of a little more than 2 years. And although he was drafted in 1968, he volunteered to be sent to Vietnam in 1970 because he wanted more responsibility and challenges.

His ambition, however, is in direct conflict with his modesty, as he continually gives credit to others. “I don’t consider myself a ‘hero’. I enlisted, I went to Vietnam, I did my job to the best of my ability, and I came home with all my parts,” he said. “All those who suffered physically and mentally, or didn’t make it back, they are the heroes.”

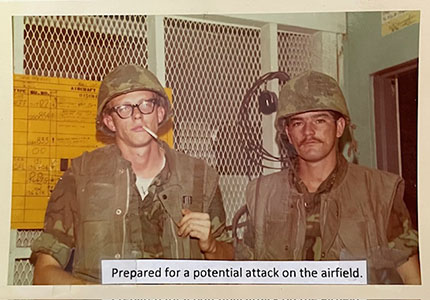

While his humility is admirable, his efforts as flight line maintenance and combat air crew member in Vietnam paved the way for other soldiers but also put him in harm’s way. On one of his first in-country flight missions, called sorties, while deploying illumination flares to help identify areas for fighter-bomber planes to target, he saw a huge ball of fire shoot past the wing. He asked a more seasoned soldier, “What the hell was that?” After he was told the enemy was shooting at them, he let loose some language he learned from his boot camp instructors.

He then learned the lights were off on the C-117 planes they used for these missions, and the engines were “unsynced” to minimize noise and vibration. The “old salt” told him not to worry because the enemy can’t figure out where they are. Hop said he eventually got used to it. Aviation played a major role in how the Vietnam War played out, and Hop was in the thick of it.

He arrived at planes by way of tractors. On the farm he helped his father overhaul tractor engines for years. Because of that experience, he signed up for the Aviation Guaranteed Program, which would offer opportunities for deep training and a structured career path for maintenance professionals. However, the Marines had something different in mind.

After Hop completed Basic Training and Advanced Infantry Training at the Marine Corps Recruit Center San Diego, and Camp Pendleton, Marine officers told him he was to report to Jacksonville, Florida, for Avionics Electronics Training. “I’m a farm boy, I didn’t know what the hell avionics even meant!” They assured me not to worry, that I would like it.

Avionics (a blend of aviation and electronics) refers to the electronic systems and equipment used in aircrafts. These systems are crucial for various functions like navigation, communication, flight control and monitoring. Hop was responsible for the safe and efficient operation of military aircraft used in the war. And yes, he did end up liking it.

After avionics training, his first duty station was Cherry Point, North Carolina as a flight line maintenance and crew member VMGR-252 KC-130F (an Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron) working mostly on C-130 planes.

He was then deployed overseas from January 1970 to February 1971, serving as a flight line maintenance and combat air crew member. His second duty station was Da Nang Air Base in Vietnam with H&MS-17 (Headquarters & Maintenance Squadron) and MWSG-17 (Marine Wing Support Group) responsible for illumination flare deployment and US2B operation pave spike monitoring on C-117 planes. Pave spikes, dropped by Phantom aircraft, are pods used to direct laser-guided bombs. Hop’s squadron monitored these via proximity sensors, flying over the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and called in bombers when they picked up a lot of noise. “I’m not sure how many of the enemy they blasted, or water buffalo herds,” he laughs.

On his first night in Vietnam at Freedom Hill, the USMC base southwest of Da Nang, he remembers looking out a window at the countryside and seeing “Puff the Magic Dragon” (the USAF AC-47 Spooky gunship) doing its job. He thought “Holy crap, I’m not even going to make it out of here tonight!” Then he realized they were miles away.

His third duty station was MCAS Iwakuni, Japan, working on C-117, C-54, US2B and TA-4F planes. His entire squadron relocated there in late July 1970. Rumor has it that when they bulldozed down their Da Nang hooches, they found a network of tunnels underneath. Hop is thankful the enemy didn’t use them while they were living there.

When his overseas tour of duty was up, he traveled back to the United States in February 1971 to his fourth duty station, back to Cherry Point, North Carolina, H&MS-27 MWG-2. Sergeant Phillips was honorably discharged on April 14, 1972, having received Marine Combat Aircrew Wings, a Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Vietnam Gallantry Unit Citation, Vietnam Action Unit Citation, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, Rifle Expert Badge, and a Pistol Marksman Badge.

He continued his drive to succeed in his post-service work. “It was tough to find a job back then, so I worked for my uncle’s hardware store for about a year,” he said. He then worked at Reichhold Chemical in the instrument department, but wanted more. In less than a year, he landed a station laborer role at Commonwealth Edison. He was continually promoted over the years, from control system technician to engineering assistant, to foreman, to how he finished his career as a temporary master instrument mechanic. He left CE at the end of 1998 after nearly 25 years. He hasn’t stopped proving valuable, recently doing much of the kitchen renovation in his house including installing the tin ceiling and cabinets.

His only regrets are tied to that ambitious streak. He knows he would have made master mechanic at CE and possibly beyond if he had a college degree. Thinking back over his military career, “I wish I would have got my pilot’s license, and I wonder why I didn’t go to Officer Candidate School when I had the opportunity,” he said.

About a year after he returned from the service, he started dating his now-wife, Lois, and they married a couple years later in April 1974. They have a son and daughter, and five grandchildren.

He is proud of his service, and that he was able to follow in the footsteps of his four Marine uncles.

We’re proud of your service, too! Have a great trip to D.C.!