U.S. Army Vietnam War La Grange Park, IL Flight date: August, 2019

By Jack & Ellen Walsh, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Jim Zwit calls it the driving force of his life. The memories and impact of that evening in Vietnam are strong. His memories, and his respect for the memories of the eight fellow soldiers killed that evening are too important to be anything else but the impetus behind the major mission in his life.

Born in 1951 in Evergreen Park, Jim had graduated from Bogan High School in 1968. He started college at the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. Because of his disgruntled youth and disappointment in his unfair treatment on the school hockey club, Jim dropped out of school after 1-1/2 years. Under pressure from his parents, he finally got a “job” – he joined the U.S. Army in 1970.

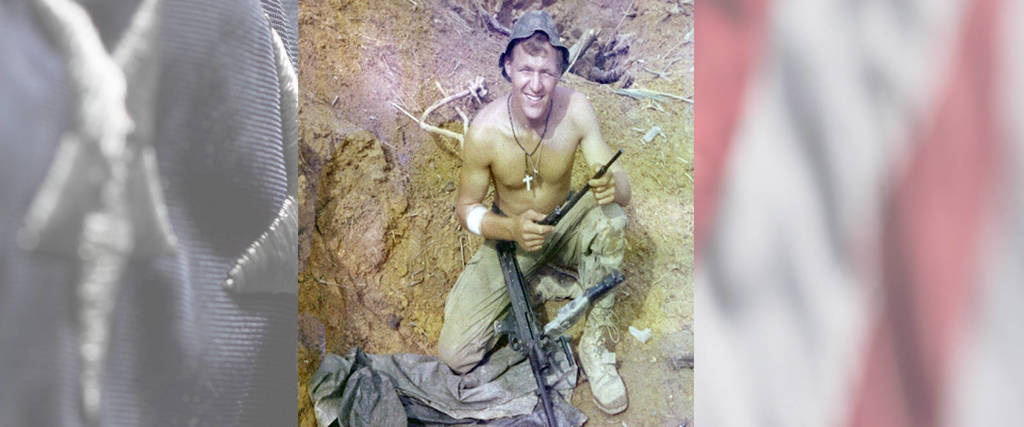

In June of 1970, Jim became part of the 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam, Northern I Corps. Weapons training had been tough for Jim – with his rifle, he couldn’t hit anything. He had no previous experience with weapons, and was a terrible shot. But then he was introduced to the M60 machine gun and he realized he could actually hit things with it. He said he didn’t mind carrying the extra 27 pounds.

On April 15, 1971, Jim was with Delta Company, 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. There were only 78 men, about 30 kilometers west of Hue, near the A Shau Valley. He was in the 3rd of three platoons as the company neared the end of a very long day. Their mission was to retrieve the body of an American soldier from Alpha Company killed two days earlier. Intelligence had indicated they could encounter about 100 of the enemy in the area.

About 6:45 pm they began setting up a night defensive position. Lt. McKenzie led a small recon around their area. Suddenly, all hell broke loose. McKenzie’s group was decimated about 100 meters forward of their perimeter, and there were screams for help. Jim deeply respected the Lt., and charged forward to help during a lull in the shooting.

He stumbled on two bodies. The first was Lt. McKenzie, who was begging for help. The second was of someone Jim knew was beyond help. Hearing enemy voices and knowing he was deep in their territory, he sprayed the area around them until he ran out of ammo. Discarding his gun, he picked up McKenzie, threw him over his shoulder, and turned to charge back to the company’s defensive perimeter. But then there was an explosion next to him, shredding McKenzie, and injuring Jim in his only exposed area – his right side. Jim believes the Lt. saved his life, taking the major brunt of the explosion and shrapnel. But Jim was still critically injured.

Jim learned later that Delta Company had ventured into a trap, with about 1500 North Vietnam Army (NVA) regulars on a hilltop full of reinforced bunkers and spider holes.

Sgt. Charles Kron crawled forward to rescue Jim, putting pressure bandages on the jagged, grapefruit-sized hole in Jim’s side. But Kron was shot in the stomach, and had to drag himself back to the perimeter. Jim knew his own screams for help were forcing blood out of his wound, so he made himself crawl back toward the perimeter, an inch at a time. Phil Brummitt rushed forward and dragged Jim by the collar toward safety. Another explosion hit, downing Brummitt and hitting Jim in the back, right leg and foot. But the two soldiers knew they had to get to safety, and despite their wounds, they got to their feet and dragged themselves over the fallen tree that marked the defensive perimeter.

It took almost four hours for a medevac chopper to be able to rescue Jim from the hot zone, dragging him on a jungle penetrator through the trees as they tried to escape the withering enemy fire. They did make it to the 85th Evac Hospital, where Jim was not expected to live.

But he did live. The battle cost Delta Company eight lives and thirteen wounded, including Jim. He lost four ribs, his right kidney, his gall bladder and 70 percent of his liver. It left him with countless scars, and shrapnel in his chest. For his courage, Jim earned a Bronze Star with “V” device and was awarded a Purple Heart.

With seventy-eight men facing 1500 enemy soldiers, it’s amazing that only eight were killed and 13 wounded. Eventually, the NVA bugged out.

Jim was in the hospital for 20 months, including 18 months at Great Lakes Naval Station, and had over 18 surgeries. He went from 195 pounds to 118 pounds.

For the next 17-1/2 years, he searched to find the family of a Nam buddy, Bob Hein. They had agreed that if one of them didn’t make it back, the other would visit their family and tell them what had happened. Bob was one of the guys that helped Jim the night he was injured, but didn’t survive the night. So Jim searched for Bob’s family, well before the internet and the extensive search capabilities we have today. Back then, Jim had to rely on information he could gather from the National Archives, the National Personnel Records Center, phonebooks, and whatever else he could garner from newspapers in what he thought was Bob’s hometown.

Purely by coincidence, after 17-1/2 years, a California contact helped Jim find Bob’s mother in Sacramento; she had remarried and had a different last name. “It was a miracle how I found this woman.” In 1988, Jim flew to California, met Bob’s mom, and they cried together. The experience made Jim vow he would contact the families of the other seven men killed.

It took him until April 15, 2011 to finally fulfill that vow, and only because of another miracle on that day. It was the 40th anniversary of the battle. Over the years, Jim had found seven families, but had been frustrated in not finding the eighth, the family of William Ward, regardless of what he tried.

On that day, Jim and four of his buddies were at the Vietnam Wall, Panel 4W, remembering as they do every five years on the anniversary. They noticed a woman leaning down, trying to find a name. Jim couldn’t help but tap her on the shoulder: “Can I help you find a name?” She said, “I’m looking for William Ward.” Jim was stunned, but finally started a conversation. She was married to one of William’s cousins. Jim thanked her for remembering the anniversary. She asked, “What anniversary?” It turned out she was from Hampton, Virginia, attending her grandchildren’s Grandparents Day. She had spontaneously decided to visit the Wall which she had never seen. Jim believes it was again only because of divine intervention that he was finally able to fulfill his vow.

Jim’s mission has evolved, but it really hasn’t changed. Its primary objective is to never forget his fallen comrades. But it has expanded greatly beyond just the eight families. He actively maintains contacts with his fellow soldiers that were there that night in April. Jim regularly organizes gatherings of his fellow veterans. Many have become close personal friends, including the pilot from the medivac chopper that rescued him that night, all at great peril to themselves. (That rescue is a whole story in itself.)

However, Jim’s mission now includes educating as many of the next generations as he can reach. Several times a year, he speaks to entire classes at several high schools and elementary schools in the Chicago area. He is regularly a guest at veterans’ events and municipal veteran memorial commemorations. And of course, he’ll tell the story of his experiences to anyone that is interested. Several media outlets have listened over the years – WTTW, PBS, the Chicago Tribune, WGN Radio, the New York Daily News, Vietnam Magazine and LTTV. Fascinating to watch and read – search YouTube for Jim Zwit and you’ll be amazed at the stories you will find.

Jim’s post-war journey has not been easy. Jim has had counseling for PTSD. During his first visit to the Wall years ago, he almost vomited from the stress. Jim says, “The most important thing to me is the remembrance of my friends and the rest of the guys that were killed in Vietnam. It’s the driving force in my life.”

Jim’s mission of honoring the fallen is ongoing. He continually remembers his brave buddies who didn’t come home from that battle. He teaches younger Americans about the good and bad of war, about the heroes that gave their all and about the heroes that still live among us. He shares their stories of heroism.

And that is an important lesson for all of us: the best way to remember and honor the sacrifices of our veterans is not only by saying a sincere thank you, but also by teaching all of those around us what our freedom has cost, and what our freedom means.

Jim lives with his wife, Graciela, in La Grange Park. He has three sons, a daughter and three granddaughters; he is so very proud of all of them.