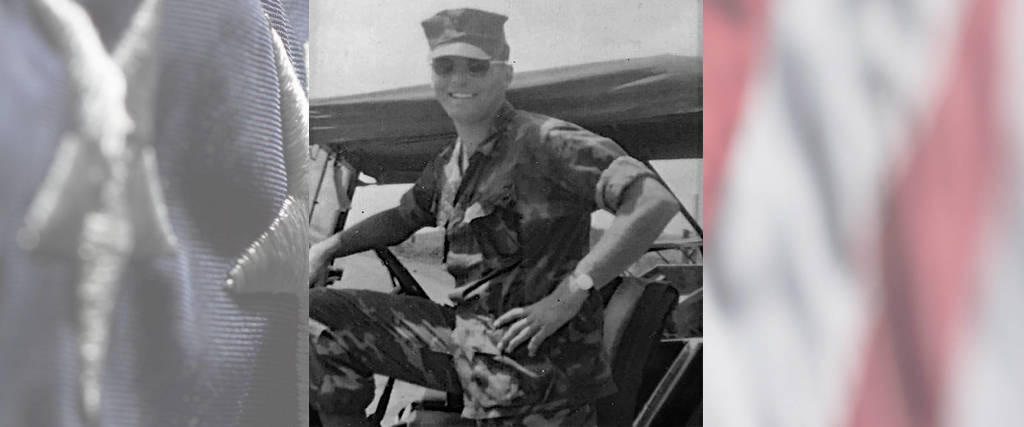

U.S. Marine Corps Vietnam Aurora, IL Flight date: July, 2019

By Charlie Souhrada, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

The morning he left for the Vietnam War, John Aister’s father drove him to the train station and left him with words of wisdom he never forgot. “My dad was a World War II veteran and knew what I was getting into,” John says. “He started crying and said two things that were always in the back of my mind: Come back home and There will be a day when you appreciate water and bread.”

John was born and raised in Aurora. His dad, John F., worked as a milkman for Oberweis Dairy, while his mom, Anne, kept house and worked part-time in the dairy’s sundae shop. This allowed her the flexibility of being home for the family, which included John’s brother and three sisters. “We lived in the greatest neighborhood, played every sport. It was an amazing time to grow up. We thought we had the world!”

After graduation, John went to work repairing lawnmowers in his grandfather’s shop and worked as an engineer, but quickly found out he didn’t like office work. He went back to work with his grandfather, making four times as much money, doing what he loved with a man he adored. Later he took his mother’s advice and looked for steady work. He applied at ComEd and the human resources manager hired him on the spot. The next day, he was out reading meters.

While reading meters in Glen Ellyn, he ran into Marlene, a childhood friend, and they started dating. Around this time, an older cousin joined the Marine Corps and influenced John’s decision to enlist. “When my older cousin came home on leave, it was clear that he had changed. He wasn’t a kid anymore; he was a man. It made me think it was time for me to grow up too.” He visited the HR department at work and was told that if he enlisted, his job and seniority would be waiting when he returned. John’s path was made clear.

His initial plans to enlist with the Army were dashed when he was told they had discontinued two-year enlistments. Remembering his cousin, he talked to the Marine Corps, signed up, and six days later took his first airplane trip to Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) in San Diego. Boot Camp was an eye-opening experience. “They shaved our heads, gave us each a box and told us to strip down and put everything in the box. Then they made us write a letter to Mom and Dad that said: I made it. I’m fine. I’ll contact you later! They even checked to make sure we didn’t say anything else and sealed the box!” All 175 fresh recruits then showered and, still naked as the day they were born, filed through a large auditorium with a GI seabag to receive their gear. “All the time I was thinking Why can’t I put some clothes on? Finally, at the end of the line, a drill instructor told us to get dressed and I thought I’m not arguing with this guy! He was REALLY big!”

John remembers Boot Camp was filled with constant running, climbing, chin ups and other physical tests. “They break you, then make you what they want, and you become stronger.” He now realizes the Marine Corps was preparing him to follow orders when and where it counts – out in the field. “When you’re given an order, you automatically respond,” he says. “There is no, I ain’t doing that out there!” After completing Boot Camp, he went to Camp Pendleton, north of San Diego, for battalion infantry training (BITs).

In March, 1970, John had his papers to go to Vietnam. Before he left, he took his first leave home to give Marlene an engagement ring. “She said she would wait for me,” he remembers with a smile. Soon after getting engaged, John flew to Da Nang Air Base in Vietnam. Upon disembarking the plane, he was ordered to report to company headquarters located in a tent within a different Marine base. He was issued a helmet, rifle and a flak jacket and driven to an even smaller base called “Liberty Bridge” where he waited in a bunker with another Marine for their instructions. “Four hours after arriving in country, all of a sudden a grenade is thrown into the bunker. I jumped up out of the tent and the other guy stayed in. They sent him to the rear and told me I was going to learn to walk point!” John explains someone used the decoy grenade to test the “new meat.” “I learned how to walk point that afternoon.” To walk point means to assume the first and most exposed position in a combat military formation. He walked point the very next day!

John explains that while walking point he was scared but very conscious. “You don’t walk on trails because that’s where they set the booby-traps. If you’re walking through a rice paddy, you avoid the dikes and if you come up to one, you’re the one who feels both sides to make sure it’s safe. You’re always leading the way and everyone else is 10 or 15 yards behind because if you trip something, you’re the one who’s going to get hurt!” John walked point for the next four months, occasionally serving as a tunnel rat. This meant crawling into an enemy tunnel with a .45 pistol and very little else to flush out trouble. “You’re young and fearless,” he says. “You think, I’m going to do this because I want to fit in with everybody else, and you do what you’re told to do.”

In his last three months in Vietnam, John was serving as a squad leader and felt burned out. “They asked if anyone wanted to be the company driver for the commanding officer, a Lieutenant Colonel. So, I visited company headquarters and saw seven guys in line for the interview – all looking sharp in starched uniforms. I had just come out of the bush. I was unshaven and looked like crap, but I got in line. This sergeant major started reaming me out for looking like I did. Then, the Lieutenant Colonel asked why I wanted to be the company driver. I said, because I’ve been sleeping on the ground for nine months now and I’d like to sleep on a cot. He told me to get cleaned up, I was the new company driver!”

As driver, John also served as the Lieutenant Colonel’s right-hand man and bodyguard. This meant when the U.S. government began pulling the Marines out of Vietnam, John flew with the Lieutenant Colonel ahead of his company into Okinawa, caught a commercial flight back to Los Angeles and eventually arrived back at Camp Pendleton. There, he worked with a team to prepare for the company’s return by ship two weeks later.

One morning in September of 1971, John surprised his mom and dad and returned home, just like his father had begged him to do at the Aurora train station two years earlier. “You appreciate everything,” he smiles. “You’re there for a year and you wouldn’t think it’s going to be like that but everything – driving a car, going to church, even a flushing toilet, wow! It takes a while, but you appreciate everything.” Later that day, he remembers waiting outside Marlene’s apartment until she came home from work. “I sent her every one of my paychecks from Vietnam and just over a year after we were married, we were able to buy our first house because of her – she had saved all of it!”

John is now officially retired from Com Ed and will soon celebrate 48 years of marriage with Marlene. They appreciate everything in life, especially their two children, Nicholas and Megan, and their first grandchild, Jonathan James. He is excited about his upcoming Honor Flight, having witnessed his father’s own Honor Flight experience as a WWII veteran several years ago. “A few years before he died, he went to D.C. with Honor Flight Chicago. When he came home from his trip, he was just beaming! It was unbelievable!”