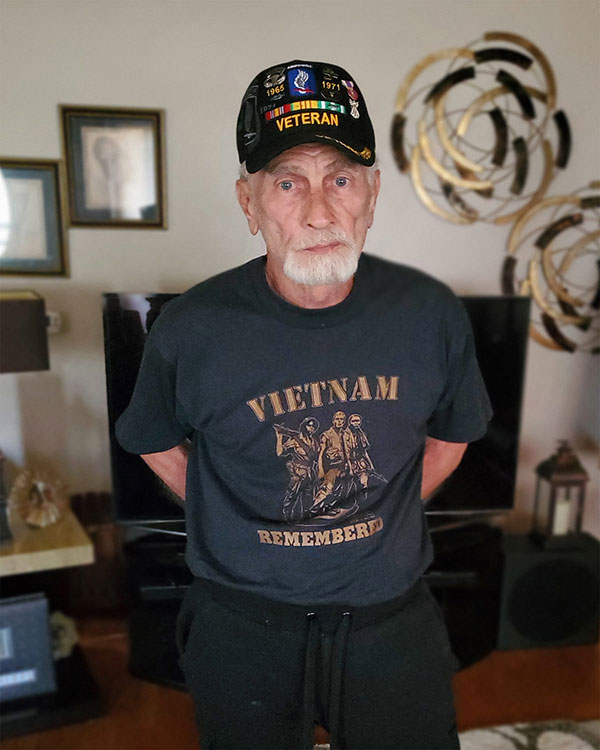

U.S. Army Vietnam War Harwood Heights, IL Flight date: 10/27/21

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

John “Rizz” Lapo’s toughness, acquired on the streets of Chicago, served him well in the jungles of Vietnam. Rizz was born in New York City in 1948 and moved to Chicago before his first birthday. He was raised by his mother but did a lot of his growing up on the streets of the west side of the city. The 1960’s were a turbulent time, especially in his neighborhood, but he enjoyed those years. The group of boys and young men he was a part of played baseball, hung out on street corners, and made sure that nobody came into their neighborhood to cause trouble. He attended Austin High School and says he could’ve been the quarterback of the football team, but instead was tempted by the life of being cool on the street corner. He dropped out of high school his junior year at which point he moved out on his own and went to work in a factory.

Because of some minor run-ins with the law, his draft status was 1Y, which meant that he was unlikely to be drafted. However, when a good friend of his was drafted, the two of them agreed that they’d go into the army as buddies, with Rizz as a regular Army volunteer. He enlisted in April, 1968 and signed up to be in the Airborne. His Basic Training was at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri; early on he was asked to take a leadership position. Because of the two extra weeks of leadership training, he was split up from his buddy. His buddy decided that he no longer wanted to do Airborne, but Rizz stuck with his commitment. After Basic Training, he attended three weeks of Army Airborne School at Fort Benning where he made five jumps, and earned his “blood wings.” During this time he also became a combat engineer.

After training, he assumed he’d be sent to Vietnam and was disappointed when he was instead ordered to go to Germany. In February, 1969 he arrived at Dexheim, Germany where he would spend the next three and a half months. While he enjoyed being on the track and baseball teams and liked that he was given the opportunity to do an additional eighteen parachute jumps, he became bored with the life of marching and standing guard duty. He also hadn’t joined the military to simply be a spectator, and wanted to do the most good for his country. He pushed to be sent to Vietnam, and eventually received his orders. He says the most important thing he did while he was stationed in Germany was three weeks of training to become a demolition specialist, which would be important once he was in Vietnam.

After a short leave in Chicago, he left for Vietnam, arriving at Cam Ranh in June, 1969. He was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade, also known as the herd. Rizz says the herd were “bad ass” and that it was one of the toughest and deadliest units in Vietnam. After a week of jungle school, Rizz was sent out into the field. As a combat engineer and demolition expert, Rizz would be assigned to an infantry squad or platoon. He’d look for booby traps, clear mines, and would often walk with the point person on patrols in order to identify mines or booby traps. He also set up claymore mines for ambushes. As the Viet Cong walked into the ambush, he’d trigger the claymore mine, and then the rest of the unit would open fire. He’d usually be in the field for a week or two at a time, and often went with the same units because they worked well together. For most of his time there, he was based at Landing Zone English, or Bong Son, which was the base for the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

One day he was assigned to go from one base to another and on the outbound trip he cleared mines from the road. On one return trip, he was driving a truck with a number of soldiers aboard and at the last minute, he saw a mound on the road that hadn’t been there when he swept the road earlier that day. He swerved and the truck rolled over. He sustained a concussion and several of the soldiers were hurt, but none seriously. An officer was irate and asked him what he was doing. He explained he had seen the mound of dirt and that it hadn’t been there in the morning. That didn’t satisfy the officer so Rizz took an ammunition box and threw it at the mound, at which point the mine under the mound exploded. Rather than getting in trouble, he ended up being rewarded with a three-day leave.

As a demolitions expert, Rizz was sometimes called on to go into Viet Cong tunnels. He’d usually start by throwing smoke grenades into the entrance, and by watching where the smoke came out they could see the other tunnel entrances. He recalls crawling through the tunnels, with just a flashlight and a .45, and that sometimes he’d see entire cities, with hospitals big enough to stand in. One of his biggest fears of the tunnels were the so-called “two-step vipers,” snakes whose venom would kill you within two steps after a bite.

His unit worked with Montagnard tribesmen whenever they could. The Montagnard were native people who fought alongside the Americans. He says they were great fighters who hated the Viet Cong and just wanted to be left alone. Their primary weapons were crossbows, and Rizz says they could jump from tree to tree; they were excellent trackers. His unit always liked to have one of them on point. They became close with many of the Montagnards and in fact, he and a buddy “adopted” a seven year old boy. The boy, Sid, spoke good English, and in return for doing their laundry, they’d give him half their chow. The boy even made him a crossbow.

In November 1969 the Viet Cong attacked his base at one o’clock in the morning. The attack was repulsed, but when Rizz got back to his bunker he realized that he had been hit in the ankle by shrapnel. The result was a silver-dollar sized hole as well as damage to a vein, and he was immediately flown by medevac to the military hospital at Pleiku. He forcefully pleaded for the doctor not to amputate his foot, and when he woke up in the ICU three days after his surgery, he was thrilled to see that his foot was still there. The hospital was attacked while he was there, which led to chaos and a scramble of patients. In the resulting decline in quality of care, he ended up with gangrene. After another surgery and nearly a month in Pleiku, he was transferred to a different hospital near Tokyo where he had a third operation and stayed for a month. This surgery included the taking of skin grafts from both of his legs to complete the repair of his ankle.

He returned home and was discharged in March, 1970. Throughout much of the 1970’s he worked in bars on Rush Street in Chicago, as both a bouncer and a DJ. He was sometimes referred to as the Mayor of Rush Street in those years. In 1976, he took a job driving trucks for the city of Chicago, which he continued doing until he was seriously hurt on the job in 1986 and was put on disability. After that, he volunteered at the VA’s Hines Hospital for twenty-two years and then was a volunteer driver for the Disabled American Veterans for several years.

He and his wife Phyllis were married in 1986 after dating for six years. He’s now retired and golfs three times a week. Rizz was in Vietnam for six months and almost all of it in the field. The impact lingers to this day and in addition to issues with his injured ankle, he has PTSD, hepatitis B and symptoms of agent orange exposure, which he says was like antifreeze raining down on him. There’s also a feeling of guilt as he did a huge amount of damage to the enemy. Overall, though, he says that he saved more lives than he took.

Rizz, Thank you for your brave service to your country. Enjoy your well-deserved day of honor!