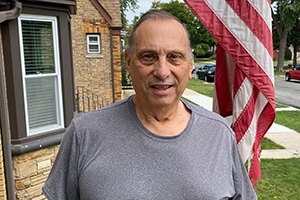

Marines Vietnam War Chicago, IL Flight date: 09/20/23

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Joseph Lombardi was born in Chicago in 1947 and raised in the Cragin neighborhood on the northwest side of the city. His father had served under George Patton in World War II and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. Growing up, Joe says that “his whole world” was physical fitness, and that is still true today. Upon graduating from Holy Cross High School in 1965 he enrolled at Wright College where he majored in chemistry, which is something that had always interested him, and minored in physical education. His enrollment entitled him to a draft deferment.

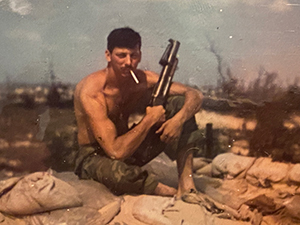

In early 1968, when Joe was in his second year of college, two of his friends, Danny and Bobby, told him they were going to join the Marines. They said the three of them could join and would stay together under the buddy plan. Joe wanted to fight for his country so he signed up with them. The Marines appealed to him because they were the toughest and most rugged, and if he was going to join something, he wanted it to be the best. Bobby came down with appendicitis and couldn’t train with them, but Danny and Joe went off to boot camp in the summer of 1968. They were classified as MOS 0311—infantry riflemen.

Boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego was tough, but because Joe was physically fit he found it easier than many of the other men. He was an athletic 6’4”, 175 pounds and before the start of training, he had already maxed out his physical fitness score. He was even put in charge of helping to train a group of men who were having difficulty meeting their physical fitness requirements. After boot camp and Infantry Training Regiment, Joe went home for a 20-day leave. At the end of it, as he and Danny were walking on the tarmac at O’Hare toward the plane that would take them overseas, Danny stopped and said, “I’m not coming back.” Joe tried to give him encouragement, but Danny was insistent.

Once in Vietnam, he and Danny separated, with Joe assigned to the second battalion, ninth Marines, Third Marine Division, which was part of I Corps. He landed at Da Nang in January 1969 and eventually was helicoptered to Vandergrift Combat Base (also known as LZ Stud). A tracer bullet ripped through the helicopter as they neared the LZ, but fortunately the LZ was only attacked a few times while he was there. One mortar attack cost a friend his leg, and in the same attack, a piece of shrapnel went in one side of Joe’s forearm and out the other. The corpsman bandaged it and gave him penicillin, but Joe didn’t follow up on it so never received a Purple Heart. It didn’t mean that much to him then, but now he wishes he had it. He was happy that the wound didn’t get infected because every scratch or cut seemed to get infected or lead to jungle rot. It was difficult to ever feel safe at the LZ, because one minute you might be watching a movie or eating a meal, and the next you’d be under attack.

On his first night in the bush, he took off his boots and hung up his socks to dry on some branches. Early the next morning he received a kick in the stomach from his sergeant who explained in a not-so-subtle manner that you can’t take your boots off in the bush—did he think that the enemy would wait for him to put them back on if they attacked? Joe says that he eventually learned to sleep pretty well in the bush, despite the mud and filth and bugs and the occasional rat scampering over his chest. He and the other men of his rank rarely knew the bigger picture of what was happening—they just did as they were told. They’d usually spend some time at an LZ, helicopter out into the jungle on a search and destroy mission, and then spend two or three weeks there, looking for the enemy or weapons caches. With a few exceptions, they weren’t involved in large-scale firefights and instead were subject to ambushes and harassment. Walking point was the worst, because sometimes the brush was so thick that the point man would have to use a machete and didn’t have his weapon. The point men were also the ones most likely to be killed by a sniper or step on a booby trap.

LZ Stud was used to support Operation Dewey Canyon, which was an effort to disrupt the supply line of the Ho Chi Minh trail. Joe says that this trail was ingenious, with interconnecting roads, paths, tunnels, and bunkers. During this operation, Joe spent over 30 straight days in the bush and his unit discovered a large amount of enemy weapons and ammunition. They patrolled a wide area including, they later found out, venturing into Laos. Their superiors ordered them not to tell anyone, especially the press, that they had crossed the border. As part of this operation, one day his company was ambushed from the top of a hill. His platoon was ordered to advance up the hill, fighting all the way. When they reached the top, they found numerous dead Marines from a different company and discovered that the enemy had retreated to the safety of caves and bunkers down the other side of the hill. Joe’s lieutenant asked if anybody had grenades, and Joe answered that he did. He then placed a grenade in his right hand, pulled the pin, put his M16 in his left hand, and ran toward the cave firing full auto. He threw the grenade into the cave and then emptied his magazine into it. Once the shooting stopped, three enemy bodies were pulled from the cave.

In September, Joe received a letter from home. These letters were usually written by his mother but this one was in his dad’s handwriting, so Joe knew something was wrong. He opened it and found out that Danny had been right—he wasn’t going to come home. He had been shot in the head by a sniper and died.

Joe’s Division left Vietnam in late 1969 and he then spent six weeks in Okinawa before coming home in January 1970. He considered reenlisting but wanted to get his civilian life re-started. He tried to go back to college to resume his studies, but after combat it was difficult for him to concentrate. While his parents were very supportive, he struggled to adjust to city life—everything was different after being in combat. He eventually dropped out of school and worked at several companies in the chemical field. He had been engaged in 1967 to his high school sweetheart and they married in 1970. They had one daughter but were divorced after three years.

Joe had always considered being a police officer, and in 1977 he was accepted into the Chicago Police Department. Many former Marines ended up on the force, and it was nice for Joe to have something in common with his fellow officers. He enjoyed his time on the force, and his beat even included the house he grew up in. He started a side business doing tree maintenance and eventually earned the nickname “Chainsaw”. He’d work a full shift as a policeman, then change clothes, get in his truck, and trim trees until it got dark. At 7:00 AM, he’d start the process over. A lot of the work he did was for other policemen, and while he liked to help them out, he says they weren’t always the best customers in regards to paying him for his services.

Joe retired from the police in 2007 at age 60 and with over 30 years of service. After his parents passed away, he moved into their house, the same one that he grew up in. He set up a gym in the basement, and despite two knee replacements he works out all the time, usually lifting weights or riding a bike. He says he can’t accept the fact that he’s not young anymore but sometimes his body lets him know. He still trains people who want to join the police force, and he also attends weekly meetings of a group of 50 or 60 former police officers and veterans, mostly Vietnam vets. He finds comfort in their shared experiences. And after all these years “Chainsaw” still does tree maintenance work, usually for police officers (and they still don’t pay him). He also is an usher in the church that is affiliated with his grade school from the 1950s.

Joe originally applied to go on an Honor Flight nearly four years ago along with three other men. Sadly, the other three men all died in the interim. He doesn’t know what emotions he’s going to have on the flight but is comforted by the fact that so many other Vietnam veterans will be there. His house is full of memorabilia from the Marine Corps and the Police force, and other than family, those are the two things that he’s most proud of. Each of these mementoes has a meaning for him, and despite some painful experiences, there are also a lot of good memories. He knows and understands that many veterans want to forget Vietnam, but he wants to remember his service to his country, which is one of the reasons this Honor Flight is so important to him.