U.S. Army Korean War Park Ridge, IL Flight date: May, 2019

By Wendy Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

It was 1944 and communist forces were moving into Romania and Bulgaria. Word of harsh treatment by the Russians in those countries was spreading through Yugoslavia where 13-year-old Matthias Burger and his family were preparing to flee. “We packed up our horses and wagons and went to Germany,” says Burger. Being of German descent, it seemed the safest thing to do; the family stayed there through the end of WWII. Five years later, the Burger family emigrated to the United States. They had to be thoroughly vetted by the U.S. Government, and have assurances that jobs awaited them here in the states.

Before leaving Germany, Matthias Burger, by then 18, signed a paper that he would be willing to serve in the U.S. military if necessary. Fourteen months after arriving in Chicago, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. “It was a necessary thing to do,” says Burger. “I was happy to do it, since the American Government gave us a chance to start a new life. We lost everything back home in Yugoslavia. The communists took everything away from us.”

Although Matt had been attending night school to learn English before being drafted, he picked up a lot more during his four weeks of Basic Training in Hawaii. Learning English in the Army gave Burger a colorful vocabulary to say the least, but he was a quick learner. “The first time I heard people yelling ‘chow time’ I didn’t know what it was. Everybody started running, so luckily I tailed along and found out.”

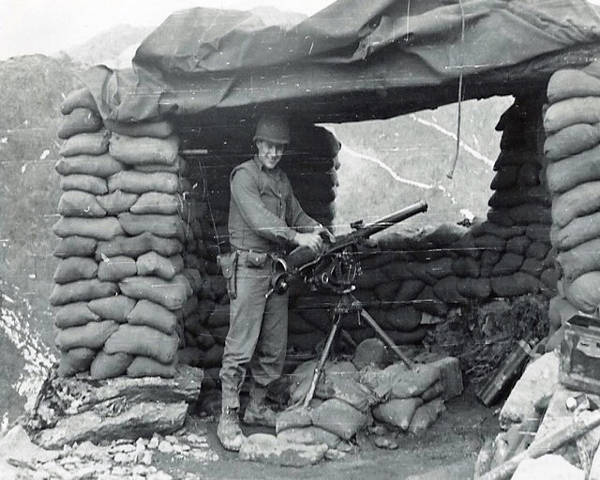

Cpl. Matthias Burger was sent to Korea and assigned to G Company, 180th infantry regiment, 45th Division. In the spring of 1952, Matt found himself and his fellow soldiers on the front lines. Positioned just north of Kaesong, on the western side of the Korean peninsula, Burger was a 57mm Recoilless Gunner, and later added the .50 caliber machine gun to his repertoire. As squad leader, he carried and fired the heavy machinery, while seven other squad members carried the ammunition. Unlike other rifles, the gun was fired from atop the shoulder rather than in front of it, and the lack of recoil saved injury to the shoulder. It did, however, cost Burger some of the hearing in his right ear.

Although his squad moved around in the early weeks, they became fairly stationary in the latter months of his time on the front lines. They dug their own trenches and built their own bunkers with sandbags and the few trees left on the terrain. “In the trenches it got all messy and dirty,” says Berger. ”Sometimes you could put your clothes out and they would stand all by themselves.”

Quite often, Burger and another gunner assigned to the 50 mm gun would set up their weapons to offer cover fire to infantrymen sent out into the “no man’s land” in the dark of night, often not knowing who or where the enemy was. “I’d rather fight the Chinese than the North Koreans. They said if you get caught by North Koreans, it was questionable if you would stay alive. You had a better chance with the Chinese.”

On a May morning in 1953, as he sat at the front lines, he got word that he was going home. With just 24 hours notice he packed up his gear, retreated to a holding area, turned in his weapons and uniforms and was sent home to Chicago. With still a few months left of fighting going on in Korea, he is still unsure why he was discharged at that time.

Not long after his return to Chicago, Burger met his wife Martha. He became a technician for Geiss America, a onetime Chicago area importer of cameras and lenses. He and Martha moved to Park Ridge in 1980. They have been married almost 62 years. Together they raised three children and enjoy three grandchildren.

Among Matt’s medals are two Bronze Stars, but he insists he doesn’t understand why he got them. He is adamant, however, that his military service for the United States was a promise kept and he is proud to have served.