U.S. Navy Vietnam Mount Prospect, IL Flight date: June, 2019

By Carla Khan, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Although he had been old enough to be drafted right after graduating from J. Sterling Morton High School in Cicero, Illinois, Robert (Bob) Bruzek received a deferment because he was supporting his mother. Bob did not sit around idling his time away, instead he continued his education. He had already taken classes in printing, automotive (a skill that came in handy many decades later), metals, and electric. Electric was by far his favorite. His dad, as a Union electrician, was able to secure a position for him as an apprentice. Bob finished his training in four years, and just when his deferment was due to expire, rather than waiting for his draft notice to arrive, he went to the recruiter’s office to discuss where he would fit best.

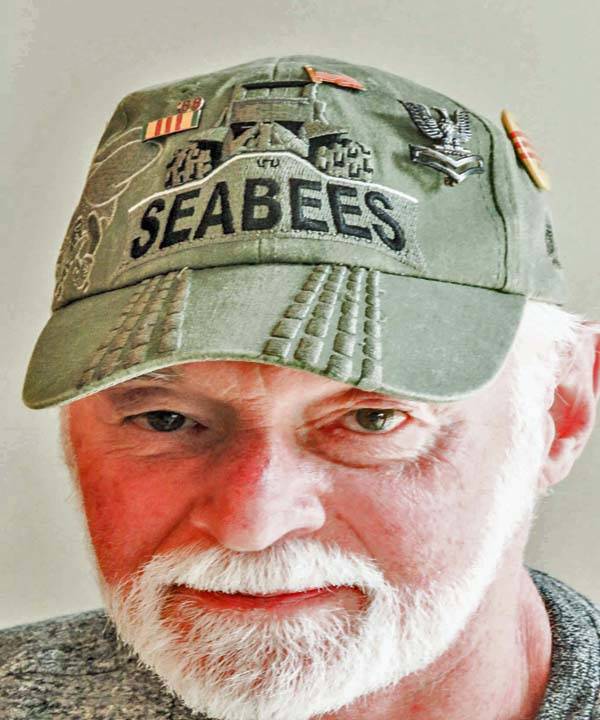

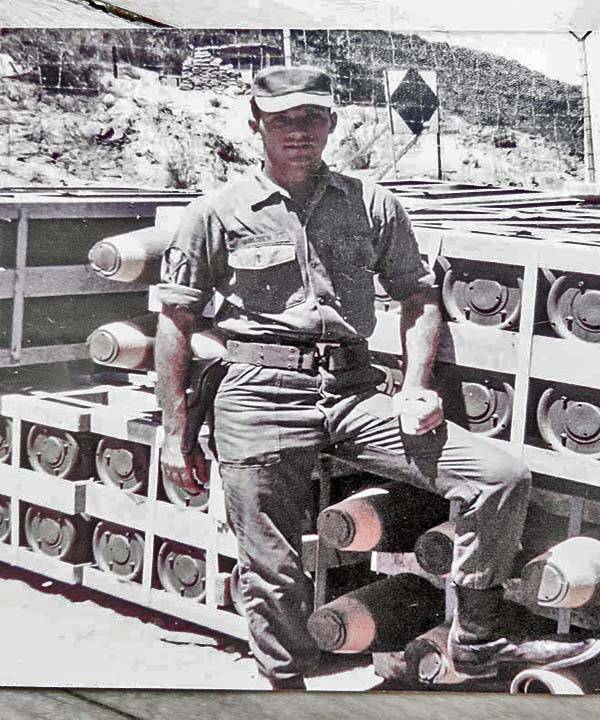

After some testing and a discussion, the recruiter mentioned that, because of the escalating war in Vietnam, the Navy Construction Battalion (the famous Seabees) needed men, and with his education and background Bob would be a perfect fit. He enlisted on the spot and before he knew it, he was reporting for Boot Camp in Quonset Point Naval Base, Rhode Island. For two months he studied and nearly memorized the famous Bluejacket’s Manual, the basic handbook for Navy personnel.

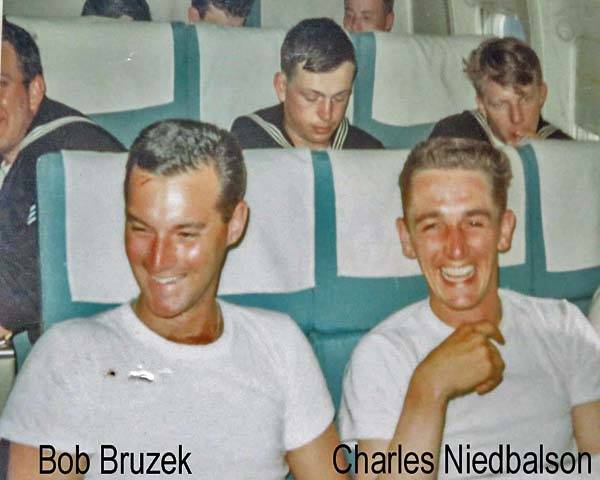

After graduation, a brief visit home, and two weeks of heavy weapons training at Camp Pendleton, he arrived at the Port Hueneme Naval Base, California. From here he flew on a World Airways charter to Da Nang. During training, he had become best friends with Charles Neidbalson from Ohio and during the next few years, they always stayed in touch and looked after one another.

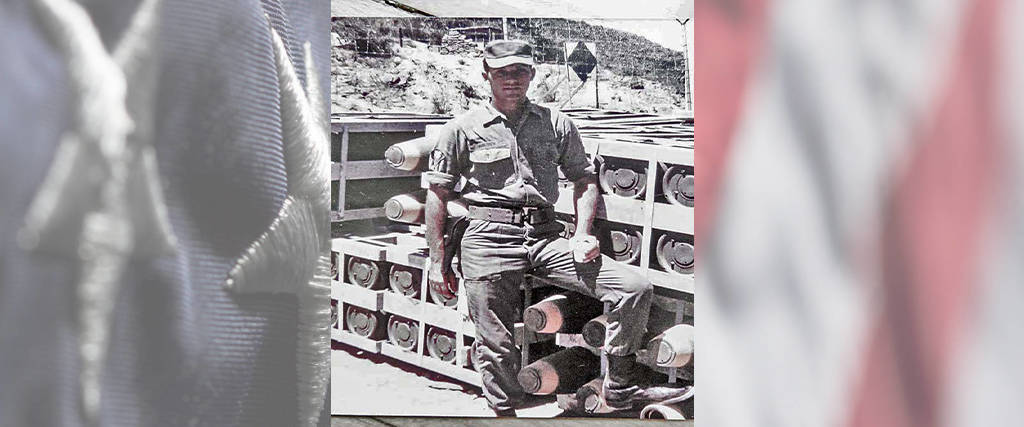

Four months after arriving in Vietnam, Bob received orders to report to Phu Bai. He was assigned to the team that looked after the four enormous 750 KW generators that provided power for the nearby Phu Bai Airport, the Marine Air Corps headquarters, and the Military hospital. In addition, there were rows of refrigerator units that stored food for the troops. The generators were so huge that it would take two cranes to lift just one of them. One generator was always working, while the second was on active parallel stand-by so that it could take over without even a split-second power outage. Of the two remaining generators, one was a backup and the other was for routine maintenance. A team of four Seabees, a Chief, a couple of Navy mechanics, and three specially trained Korean techs worked shifts that were 24 hours on, followed by 12 hours off. It was considered too dangerous to leave the protected area, so all time was spent on the base.

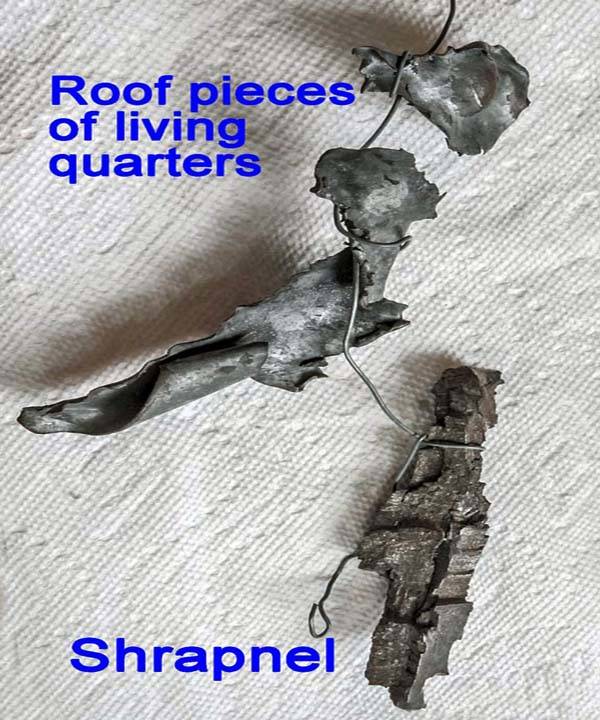

While the area was not considered a direct enemy target, they often were in the line of fire and watched rockets go overhead. Occasionally, there was a hit close by and although the generators were protected on all sides by sand dams, shrapnel caused damage to men, buildings, and equipment. This damage occurred especially during the Tet Offensive when there were daily attacks. Because of the thunderous noise of the nearby protecting artillery, the crew used hand signals for communication. New crew members were taught to bang signals on the sides of the generators to alert those at work inside when they had to run for the bomb shelter.

In spite of the stressful life, there were also highlights. The best of them was a surprise visit from Bob’s younger brother who had been working on the construction of the Cu Chi hospital. As it turned out, their service times overlapped by three months. His brother knew where to find Bob, hitched a ride on an airplane and a military truck and suddenly showed up when Bob was playing cards with his buddies. It was a memorable surprise and they spent 14 hrs straight, talking.

Another pleasant fact was that the generators were not far from a huge Marine “chow hall” and bakery, and at 1 a.m. the scent of freshly baked bread would waft over to the generator maintenance area. As the cooks knew really well who it was who kept their ovens going, they always had some bakery items that “did not meet standard” and found their way to the Seabees. Occasionally, when the food chain worked really well, the Seabees managed to “trade” items for boxes of huge steaks meant for the pilots.

The climate also took some getting used too. During the three months of pouring monsoon rains, the soft and dusty earth turned into a foot of mud in which vehicles got stuck. Each Seabee had three pairs of boots: one to wear and the other two were stored inside a wooden box with a light bulb that helped them to dry out.

When the end of their service time came near, the men often would hang a small beaded chain off one of their pockets and snip off one bead each day to show their countdown. Bob’s chain had already become pretty short but he still had not received his discharge orders when his good friend, Charlie called him, “Bob, your name is on the list. You are leaving soon. Get yourself over to Da Nang!” Bob did not wait and went home almost immediately.

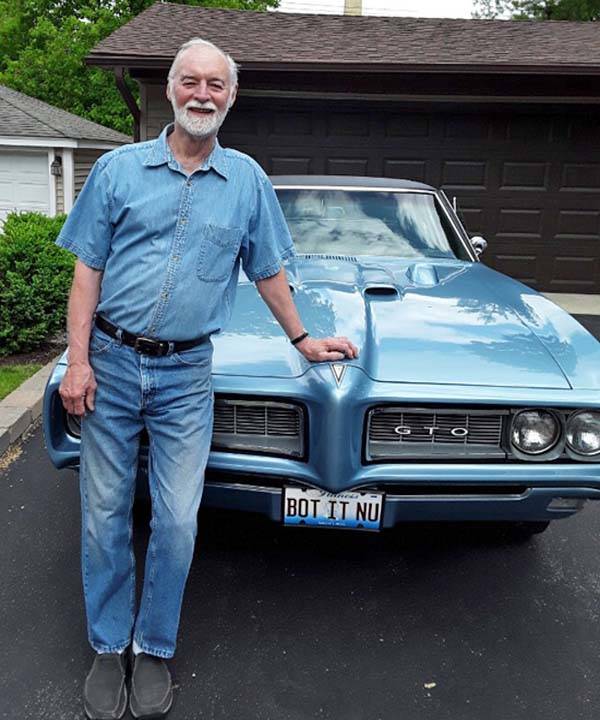

He surmised, “We went because the Government wanted us to go. Unlike the WWII veterans, we didn’t go home in large groups, we returned individually. We tried not to be noticed.” After spending two weeks at home enjoying civilian life, Bob contacted the contractor he had apprenticed for earlier and immediately received a job offer to work at the construction of four huge printing presses. He had to be able to start the following Monday and he’d need a car for transportation. That is how in June 1968, he became the proud owner of his beloved ’68 Pontiac GTO, which he still has to this day. The Pontiac still looks brand new, thanks to three complete restorations. Bob feels that his time in Vietnam contributed to his aging process. He still becomes very uneasy at the sound of helicopters and gets startled by sudden, loud noises.

Bob enjoyed his career as an electrician. He always likes spending time with his daughter, a son and three grandchildren. In 1994, he met Sharon, the love of his life, and they are enjoying their retirement together.