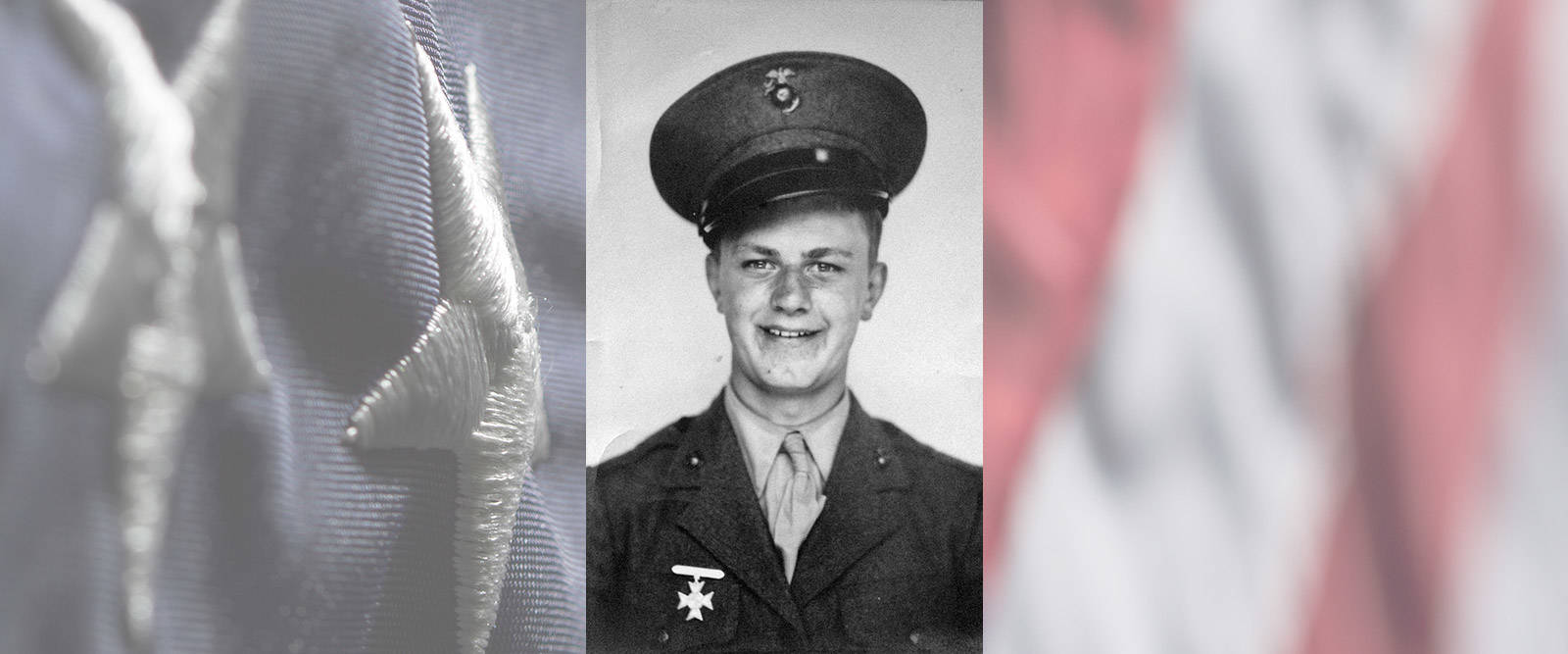

U.S. Marine Corps WWII Libertyville, IL Flight date: 06/06/18

By Wendy L. Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, Okinawa, Iwo Jima – giant names in the annals of World War II. But for 93-year-old Alvin Izbicky, they were very real places. Alvin had infiltrated and fought on all of those Pacific Islands before his 21st birthday.

Alvin, his parents and 8 siblings, moved to Chicago from a Pennsylvania farm when he was quite young. He was only 16 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, still too young to enlist. But that didn’t deter him from leaving high school a year or two later, and enlisting in the Marines, even though three of his older brothers were already in the Army.

With the critical need for soldiers in the Pacific, Corporal Izbicky underwent Basic Training aboard ship while sailing west to the Mariana Islands. After a quick two day skirmish on Tarawa where he saw his first combat, the Marines 2nd Division sailed for Saipan, where his new skills as a demolition expert came into play. “There was an unexploded Japanese torpedo on the beach in Saipan, and they wanted a volunteer. All the other guys were much older than I was and nobody wanted to volunteer, so they volunteered me,” says Izbicky. “They gave me a book about how to take the bomb apart, so I went up there and they all left. I was nervous because I didn’t know anything about it. I read the manual, then I cut the wires. When I went back they said, ‘You’re gonna do this from now on!’”

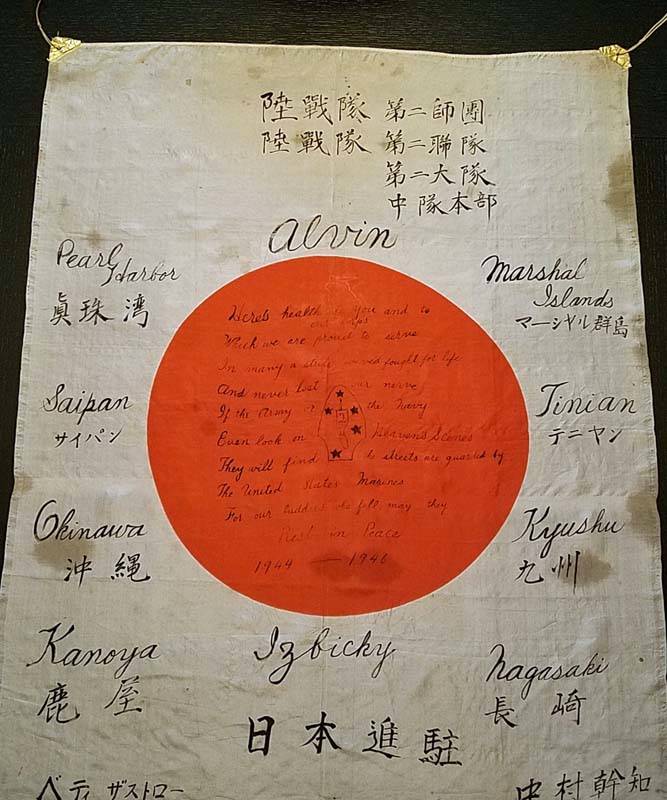

In 1944, the Allies were determined to retake the Mariana Islands from Japan. That possession would give the U.S. forces a foothold in the Pacific from which to bomb the Japanese mainland and hopefully force Japan’s surrender. Izbicky became part of a force of 39 men assigned to land on each island under the cover of darkness, scout the lay of the land and the enemy, and report back to the larger invasion force on the best places to land their troops. After three weeks of intense fighting, Saipan and its valuable airfield finally fell in July of 1944. Izbicky and his fellow demolition experts continued to move from island to island as the first wave, often becoming part of the invasion forces that followed. During one hand to hand clash with a Japanese officer on Okinawa, Izbicky was stabbed in the wrist, and still carries the scar today. He also has the Japanese flag that he took off the officer’s body when the fight was won. Every member of his platoon signed the flag.

Saipan became the base of operations for Izbicky and his fellow demolition experts for almost a year. When they weren’t on duty, they often hung out at the airbase. One day, Army Air Corp pilots invited them to take a ride in one of the new B-29 bombers. It wasn’t until they were in the air that the pilots told them they were actually on a bombing run to Okinawa. With the Marines riding along, the pilots dropped their bombs over the enemy island, then headed back to Saipan. It seemed like a successful run until they hit the runway and the plane split in two. “We were all ok,” said Izbicky. “But after we got off, they took out everything they wanted and dumped the plane in the ocean.”

On September 2, 1945, the Japanese surrendered and Izbicky became a part of the occupying forces of Japan. His job was to blow things up – hidden bombs, ships and any other explosives left around the island by the Japanese. It was there that his luck turned. “I was just ready to turn around and defuse a bomb, when BOOM! I was blown out of the cave,” said Izbicky. “I had two rings, my watch and my shoes blown off – I was in the hospital for about five months.” Two young Japanese boys working with him to find and defuse bombs had pulled the wrong cord. Both boys were killed.

Izbicky finally returned home to Chicago in 1946 to finish high school. He started eating at a local lunch spot with fellow students; that’s where he met his wife Margaret. They had been married 65 years before her death a few years ago. Izbicky chose not to blow things up in civilian life. Instead he worked at a meat market in the city, eventually buying it and building a life for his family. After 49 years he decided to retire, but he found himself with time on his hands.

With a home at Waveland and Central in Chicago, what better place to work than Wrigley Field? He started the very night they turned the lights on at Wrigley for the first time. For the next 7 years, Izbicky worked as an usher and after-game security for the Chicago Cubs, foiling more than one would-be stadium seat thief. Eventually, Alvin moved to Elk Grove Village, and now resides in Libertyville. He does not dwell on his World War II service, preferring to enjoy life today. “That was a long time ago,” he says.

Alvin Izbicky, we thank you for your brave and courageous service to your country in WWII. Enjoy your well-deserved Honor Flight!