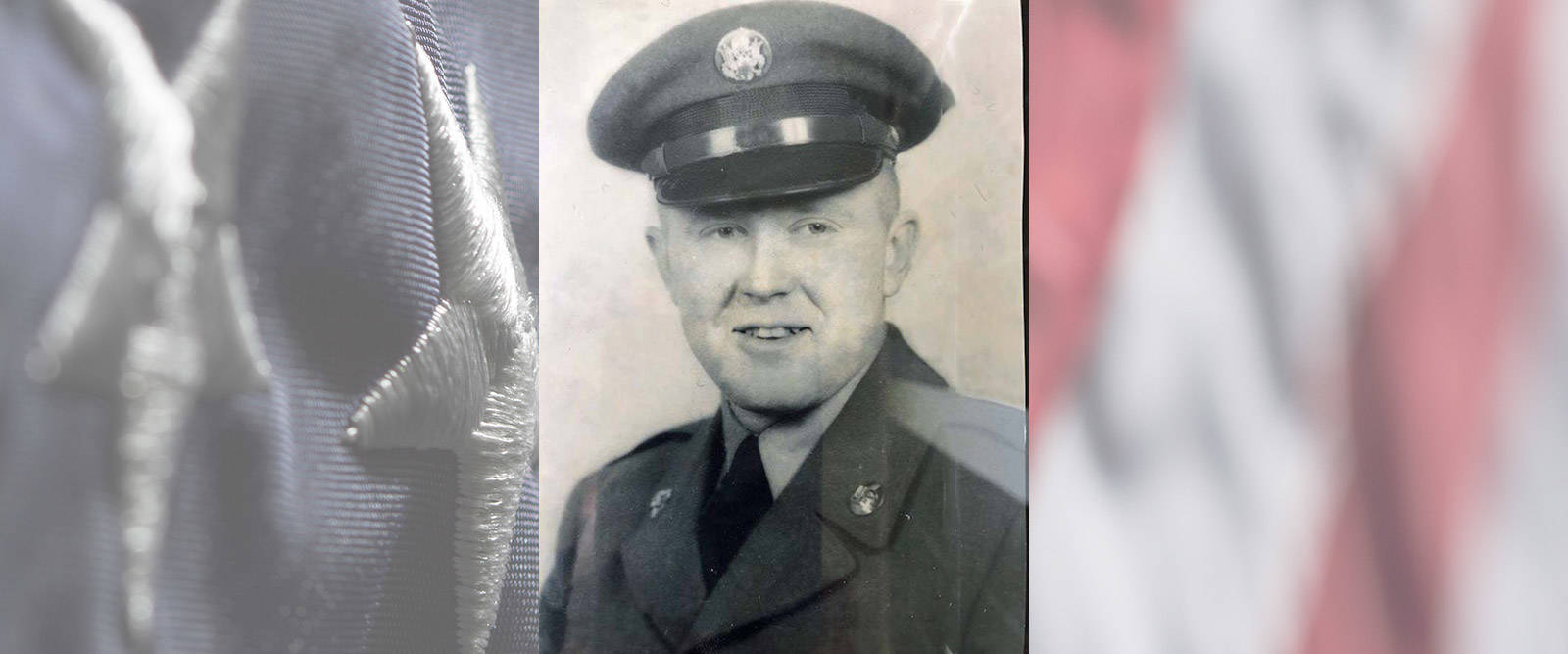

U.S. Army Korean War Oswego, IL Flight date: 06/06/18

By Charlie Souhrada, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

On March 26, 1953, one day before his 20th birthday, U.S. Army Sergeant Roger Liddicoatt was captured by Chinese soldiers, held in a small cell and tortured repeatedly until the end of the Korean War four months later. He remembers the experience, but refuses to let it define him.

Roger was born March 27, 1933, to Roger Sr. and Margaret (Peggy) Liddicoatt. At the time, his father farmed a 27-acre tract of land in Clarendon Hills, IL. Roger worked on the farm and in other part time jobs. As a Boy Scout, he achieved rank of Life Scout, earning many merit badges – including one for Morse code, which held a significant role during his military career. After high school, Roger went to work with his father at a foundry in Joliet until November 19, 1951, when he enlisted in the Army.

Upon enlistment, he was offered a role in the Army Security Agency (ASA), formed after World War II to conduct high-level electronic surveillance and intelligence gathering. “They made it sound good, and that’s why I took it,” he says. After induction at Fort Sheridan, his military service began with 16 weeks of Basic Training at Fort Riley, KS where he went through “hell” at Camp Funston with a platoon of other ASA recruits.

After Basic, he went to Ft. Devens, MA. for six months of code school. After the first three months, Roger and his platoon were flown to Ft. Benning, Georgia, every weekend, for special forces training with the 529th Regimental Combat Team (RCT). The platoon eventually learned they were heading to ASA headquarters in Arlington Hall Station, Virginia, to learn Chinese numbers and code procedures by voice. “At that point, we knew exactly where we were going and what we would be doing!” Now that he knew he was headed for Korea to intercept codes, Roger and the rest of the men were ordered to keep quiet and avoid mingling.

Meanwhile, the Army investigated his background, which included interviews back home with his parents and grandmother, even his girlfriend and her mother. He did receive Top Secret clearance. Decades later, his service record shows a 1952 enlistment instead of the correct year, 1951, possibly ignoring his year of code training. Nearly 70 years later, Roger and his family are still trying to correct his record.

By December 1952, after one year of training, Roger’s original platoon of 56 men had been whittled down to 48. “It took stamina, believe me!” Thanks to his ability to learn quickly, coupled with his prior National Guard experience, he was named the lead, non-commissioned officer (NCO) for his platoon, and sent to Ft. Ord, CA. where he boarded the troopship USS General Breckinridge. The platoon was assigned to I Corps in Seoul, Korea and received their first mission – parachute behind enemy lines from a C-47, and gather code intelligence.

“After all that training, we finally jumped in. That was the first and last time.” Two of his men were impaled on tops of trees that had been destroyed in battle. From that point on, the platoon dangerously crossed the line of departure on foot and ran. This was necessary because the platoon was equipped with specially-made intercept radios that allowed them to pick up messages. “If we thought a message was urgent, we’d crank up our radios and send a message back to group headquarters.” The platoon also carried direction finder (DF) radios, that allowed them to lock on a signal and establish the enemy’s location. “The trick was getting close enough,” he says. “More and more, they were sending messages by voice and we couldn’t pick it up. That’s why they sent us in.”

During each 3-4 day mission, Roger and his men hugged the ground as close as possible and relied on a point man to scout for trouble. “If anybody who has ever been in a war zone trying to sneak around and getting shot at at the same time says they weren’t afraid, well they’re either a damn liar or a damn fool.” A simple mistake during the platoon’s fifth mission behind enemy lines led to Roger’s capture. That day, despite a standing order not to wear any “stinky stuff,” one of Roger’s men wore deodorant and the scent compromised their position. At the first sign of trouble, he chased his men out, stayed behind to protect their retreat and got caught in a firefight. During the fight, he was wounded by shrapnel and captured. As a result, he spent his 20th birthday and the next four months as a POW until the Korean Armistice in July, 1953.

Roger readily admits he was “scared as hell” when he was taken. The Chinese soldiers wrapped a tourniquet around his leg to stop the bleeding, and slapped something mysterious on his wounds. Then, he was held in a 4’ x 6’ cell with a low ceiling, where he survived on a diet of raw fish and rice, and an occasional helping of green, spicy kimchi. “I was never away from camp and never associated with any other GIs so I don’t know where I was held.” He was released from his cell only to walk to another part of camp where he was tortured. “It was bad, terrible. I suffer from it a little bit even today,” he recalls. “But no matter what happened, I never forgot my father’s words. He would always say, ‘Never give up. Never give up.’ We didn’t and I didn’t.” When the armistice was signed, Roger was released from his cell with little fanfare and transported by ambulance to a field hospital. He had lost 35 pounds and suffered from dysentery. After three months’ rehabilitation in Osaka, Japan, he was sent back to the Korean Demilitarized Zone to monitor communications from a “hut truck.” He remembers, “I couldn’t believe it! They extended me a year and put me back out there. I thought I was going home!”

His discharge papers finally came through in 1954 when he was on a surveillance site. He hitched a ride to camp and boarded a ship back to Ft. Ord in California. From there, he flew aboard a C-47 that eventually landed at Chicago’s Midway Airport, by mistake; they were supposed to land at O’Hare. The planes reloaded, flew to O’Hare and Roger was discharged at Fort Sheridan, where it all began four years earlier.

After the war, Roger returned to home to Lisle, IL. His family didn’t know he had been wounded or captured. Because of his Top Secret clearance, he was told to write two months’ worth of letters at a time, which were then sent at regular intervals. “You’d be surprised by some of the things they asked us to do!”

His post-war career started at a plastics factory, then he drove trucks for 25 years and worked as a maintenance manager for 10 years. Well into his eighth decade, Roger continues working part-time at The Home Depot in Oswego. On July 7, 1956, he married Katherine Vedok. Together they raised their two children, Pamela and Daniel and shared pride in their two granddaughters and five great-grandchildren until Katherine’s death in 2015.

To this day, he takes pride in the fact that of the 48 men in his ASA platoon, 37 returned home after the Korean War and beat the odds. “I don’t know if God was with us … luck, I haven’t got the answer. But I’m still here and I never give up!”

We thank you, Roger, for your courageous dedication to your country. Enjoy your well-deserved Honor Flight!