U.S. Army Korean War River Forest, IL Flight date: April, 2019

By Donna Pacanowski, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

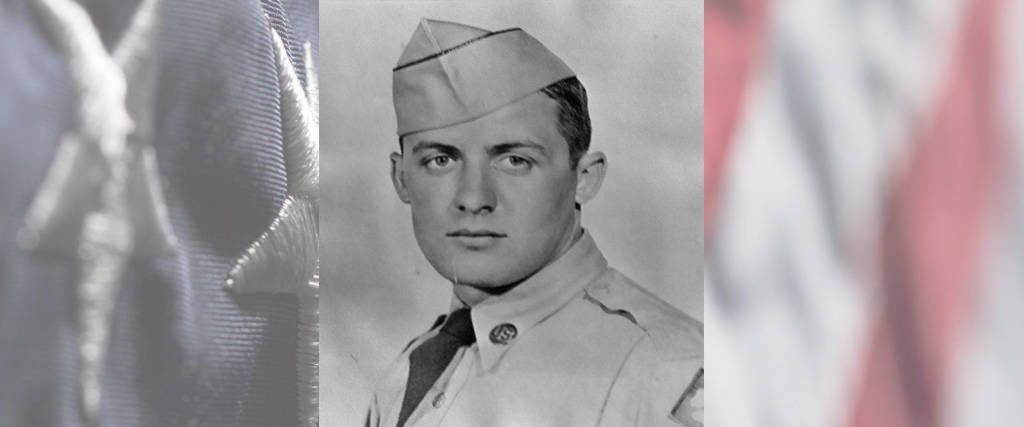

William C. Devereux, “Clarke”, was born on May 18, 1931, and raised on the west side of Chicago along with his two sisters and a brother. His parents sent him to St. Ignatius High School. He later realized that “the two greatest influences of my life were St. Ignatius and the U.S. Army.” Clarke attended Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa, on a football and track scholarship, but couldn’t outrun his draft notice.

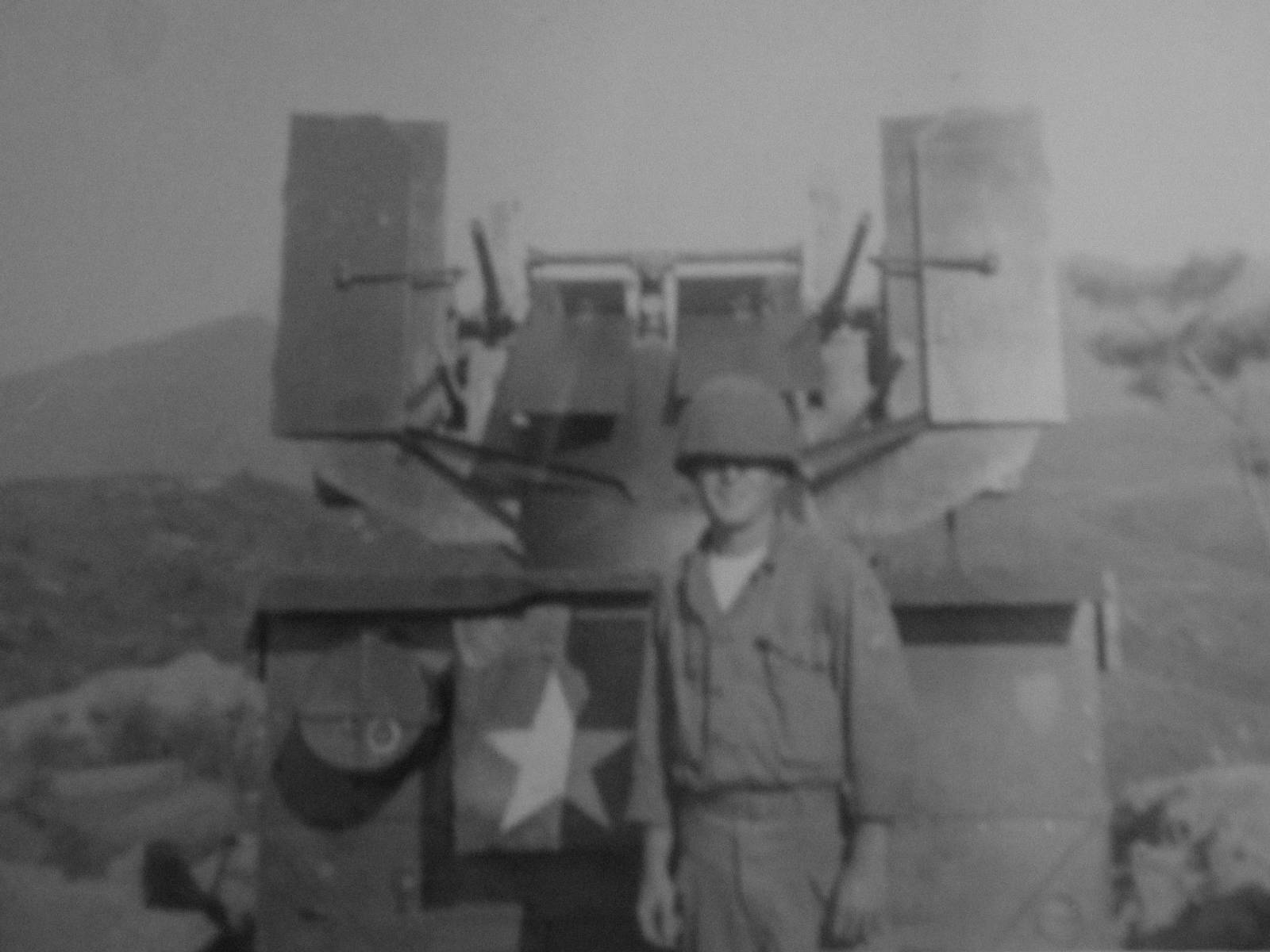

Clarke reported to Fort Sheridan in September, 1952, for induction and orientation into the U.S. Army. On the day he boarded the train for Fort Bliss, Texas, Clarke could not tell his family. Staring out the train window, Clarke recognized his neighborhood. As the train passed his house, Clarke believes he could have seen his mother at the kitchen window. At Fort Bliss, Clarke trained as a Quad-50 caliber machine gun crew member. During this time, the training cadre identified Clarke as the perfect candidate for an instructor in CBR (chemical, biological, radioactive) training. Clarke was assigned as instructor of fellow soldiers in CBR warfare at Fort Bliss and in Japan. His entire unit, the 21st AAA (Anti-aircraft Artillery Automatic) Weapons Battalion sailed for Korea. At Yokohama, Japan, Clarke left his unit to continue as CBR instructor there, while the rest of the unit joined the 25th Infantry Division in Korea. Clarke had a chance to visit Hiroshima and surrounding areas and saw the destructive power of the Hiroshima A-bomb of 1945. The entire city was rubble; only a few skeletons of buildings were standing. Thirty miles from Ground Zero, he was shown a debris pile. A door, originally part of a building in Hiroshima, had been blown there by the force of that first A-bomb explosion!

Soon it was time to rejoin his unit in Korea. Arriving in Pusan, Clarke, traveling alone and hungry, headed to the mess hall. After going through the chow line, Clarke surveyed the huge dining area, looking for a seat. Several British soldiers were seated nearby and waved him over to join them. When the Brits heard Clarke was from Chicago, the questions came swiftly. In the midst of the conversation, a surly mess sergeant rushed over and ordered the British soldiers to get their “mangy dog,” the unit mascot, out of the mess hall, or he’d kick it out himself. Insulted, one of the Brits stood up, coldcocked the mess sergeant, sat down, and continued by asking “Tell us about State Street” as if nothing had happened.

Upon arrival at the front line, Clarke asked the sergeant, “Where is the American flag?” The sergeant promptly responded, “Why don’t you just use the field phone and tell them where we are?” Clarke’s new home was a sandbagged position for his squad’s Quad-50, facing barbed wire, a battered and cratered area, and the enemy beyond. The meals were C-rations three times a day. Clarke was very apprehensive at first, but his faith and prayers sustained him.

Clarke recalls a large battle at Musan-ni. He was now a sergeant; his squad of five men was composed of two ROK (Republic of Korea), a Native American, an African American and one Caucasian. By this time, he had picked up enough basic Korean to communicate with the ROK soldiers. As the battle began, artillery shells fell around his area and machine gun tracers flew overhead. The barrels of his Quad-50 glowed as bright as white snow from the continuous firing, and the squad was running short of ammo. When Clarke radioed for an ammo resupply, the depot clerk said the armory had no ammo for Clarke. After swearing at the clerk, Clarke described the battle and told the clerk to deliver the needed ammo or to start loading his own rifle. The ammo arrived immediately!

On one occasion, Sgt. Devereux was informed by the Company Captain that General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the Eighth Army in Korea, was headed up to Clarke’s position on the ridge. Clarke prepared the Korean squad members with stories of Gen. Taylor’s heroism in WWll, when he jumped behind German lines, 24 hours before the D-Day invasion. The ROK troops were awed by the bravery of the General. The next morning, General Taylor came to the Quad-50 position. Clarke commanded his squad to attention. After an inspection of the squad, General Taylor was impressed. He questioned Clarke on the enemy disposition and Clarke pointed out the enemy strong points to the squad’s front. At the end of the briefing, General Taylor asked “Are you ready for them?” Clarke shouted, “Absolutely!” The General’s response was, “That’s what I like to hear.”

The truce was signed on July 27, 1953. Clarke received a message from headquarters that US searchlights would sweep the enemy positions three times and the enemy searchlights would sweep US positions three times, thereby both sides acknowledging the beginning of the truce. Clarke made sure his men didn’t shoot out the searchlight, as in the past.

By the end of Clarke’s tour in Korea, he was promoted to 1st Sergeant, received a Letter of Recommendation, and was offered an appointment to West Point. He politely declined, stating “I just want to go home.” Clarke used the GI Bill to return to Loras College in Dubuque. He reacquainted with neighborhood and high school friends. One of these friends was Patricia, by now, not the sweet teenage girl he remembered, but a beautiful young woman. Clarke and Patricia will celebrate 63 years of marriage this year and have been blessed with seven children and 18 grandchildren. Over 40 years ago, Clarke founded the Devco Foil Stamping and Embossing Company, where he continues to work today as company CEO.

On July 27, 1995, Clarke and his family were present at the dedication of the Korean War Memorial in Washington, D.C. He has frequently been asked if he posed for one of the faces engraved on the granite wall that surrounds the memorial, as the resemblance is so striking.