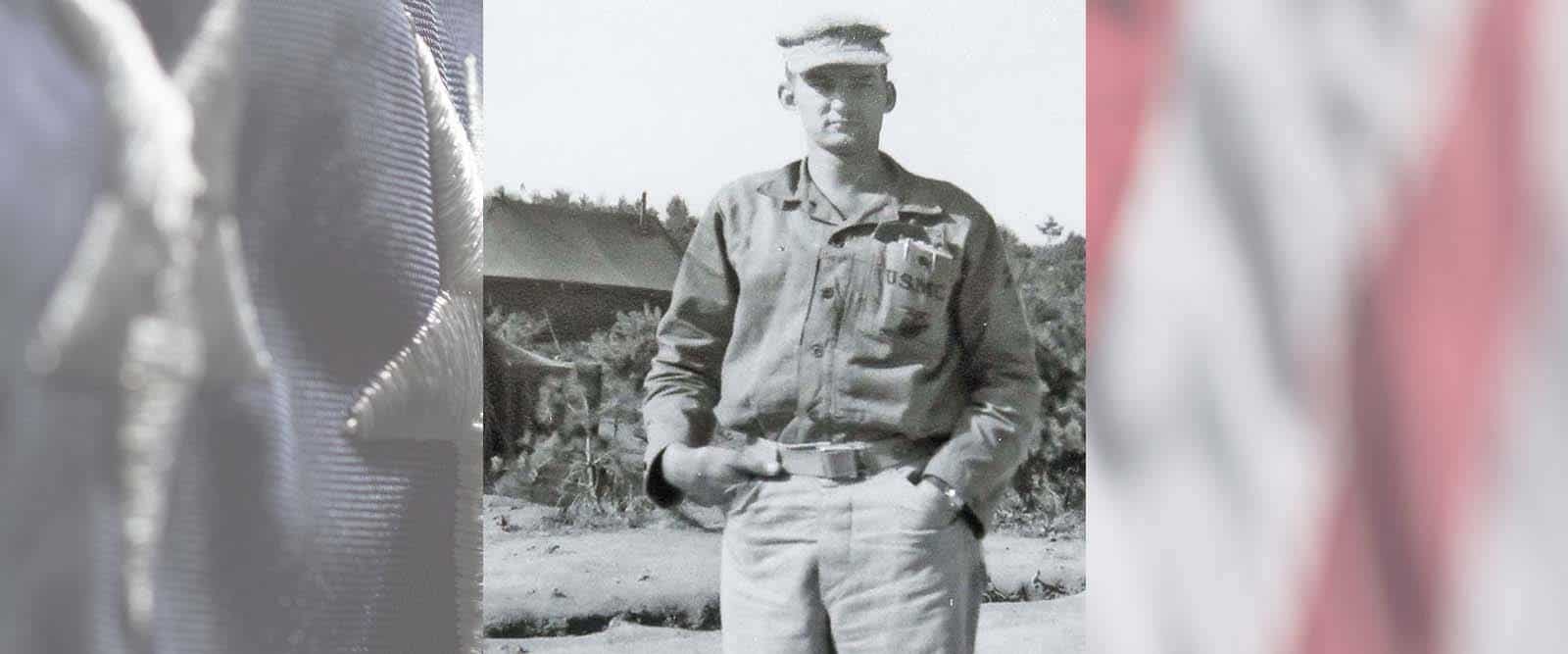

U.S. Marine Corps Korean War Chicago, IL Flight date: 07/12/17

By Carla Khan, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

It was March 1951 and the Korean War was going on. Having an older brother who served during WWII, along with being convinced that it is better to address an enemy on foreign territory than on your own were valid arguments for Bernard (Ben) Ogarek to enlist in the US Marine Corps. In his words, he was “gung ho to protect his country.” Boot camp in San Diego, CA, earned him the title of being a “Hollywood Marine.” He was fortunate to get a drill sergeant who had just returned from Korea and could fully prepare his Marines for what to expect there. Since every Marine automatically also is an infantryman, Basic Training was complemented with Track Vehicle School where Ben learned to drive tanks and landing vehicles.

Orders for Korea followed immediately and soon Ben was shipped out to Yokosuka, Japan. No time was wasted while crossing the Pacific and shooting practice occurred daily. Since Ben knew how to type, his additional duties included that of becoming the Company Clerk and Mailman. Upon landing in Japan, they were almost immediately transferred with destination Pohang, South Korea. They landed on November 6, 1951 and joined the B company of the 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalion. Using Landing Tracked Vehicles or LTV’s, they unloaded ammunition, gasoline, etc. for the 1st Marines. They were housed in tents and unfortunately the food could be labeled mediocre at best. Fortunately, however, because Ben’s tent was close to the Seabee’s encampment, they were invited to join that food line and enjoyed really good food.

With more manpower needed at the front, Ben along with 224 other Marines were transferred to the so-called “Quiet Sector” near the Han and Incheon rivers. “Quiet” was a misnomer because the North Koreans blasted “news” such as intentionally erroneous weather reports 24/7 from gigantic speakers across the river towards the Americans. The sound was relentless and torturous; to this day, Ben still occasionally hears this in his thoughts. Not to be daunted, the Marines, retaliated. At night, they would go to the Inchon river’s edge armed with their walkie-talkies. They’d get as close as they could and made sure the enemy could overhear their communication. The enemy then would send up flares so they could see and shoot at our Marines who would hide in the rice paddies. In the summer, they would lie down in the mud and in the winter, they’d hide out in the snow till the shelling died down. While the flares also disclosed the enemy’s position, the grid system provided was often incorrect because no maps were available. As a result, more than once, our Marines came under simultaneous fire from friend and foe. The best they could do was remain hidden till it was safe to move again.

Since the B company was sent out as a replacement for a Marine unit that had lost too many men, they initially improved the camp by adding trenches and building new bunkers in the hills and they moved equipment to about 15 miles beyond the front lines. Other than the thunderous shelling and the woman’s voice from across the river, it also could be eerily quiet because all trees and shrubs had been stripped from the area. No wind played through branches, no birds were around. For the entire period from April 1952 to January 1953, these Marines fought without a break through rain, snow, and ice. The uniforms issued were khaki green and it was hard to get hold of a white camouflage parka. Food was very basic as well: powdered milk and eggs along with some coffee for breakfast, Lunch consisted of peanut butter and jelly with crackers, chicken soup, and c-rations which were also served for dinner. On rare occasions, there was ice cream. Christmas 1952 was the only real dinner that was brought in and New Year’s Day 1953 was creatively celebrated by the men by mixing alcohol with baking powder. The result was a spectacular foam mountain, happily shared by all.

The fighting continued. Each bunker, on the high ground of the river, had no shortage of machine guns and mortars as well as a 150-caliber machine gun. They would spot the enemy with their binoculars and then replace the tracer bullets with regular armor. Sometimes the fire would fall short and they were supported by the 1st Army Tractor Battalion. On one disastrous occasion, the Army unit got knocked out by the enemy and the Marines stepped in by taking over the guns from the fallen men. For months, there was no respite. They were where they were needed most and did their job. There was no time to get rotated to the rear, away from the front line. There also was a shortage of non-commissioned officers. At the end of December 1952, when it was time to go home, Ben got promoted to Sergeant and asked to stay on till a replacement was found. He stayed on for another 3 months without a break.

Then, finally it was time to go home. He traveled in the back of a truck to Inchon and returned to the United States by troopship. The food was ok and the bunks were 18″ apart, but, he was alive and on his way home! Surgeons in a military hospital “put him back together” in Ben’s words, with a new nose, a new jaw line, and repaired various herniated body parts. Ben, who put his life on the line for his country, had along with severe physical injuries, also acquired memories that would haunt him off and on for the remainder of his life.

Resilient as a real Marine, though, Ben continued where had had left off before his time in Korea. He took advantage of the GI Bill, went back to school and obtained a degree in Chemical Engineering in the record time of 3 years and met a wonderful girl by the name of Sandy. Ben had a great career doing hands-on engineering work, which he really enjoyed. Sandy and Ben had a good life. They raised 5 children and he is now enjoying his 7 grandchildren.

Ben, we thank you for your service. Enjoy your well-deserved Honor Flight and finally, Welcome Home!