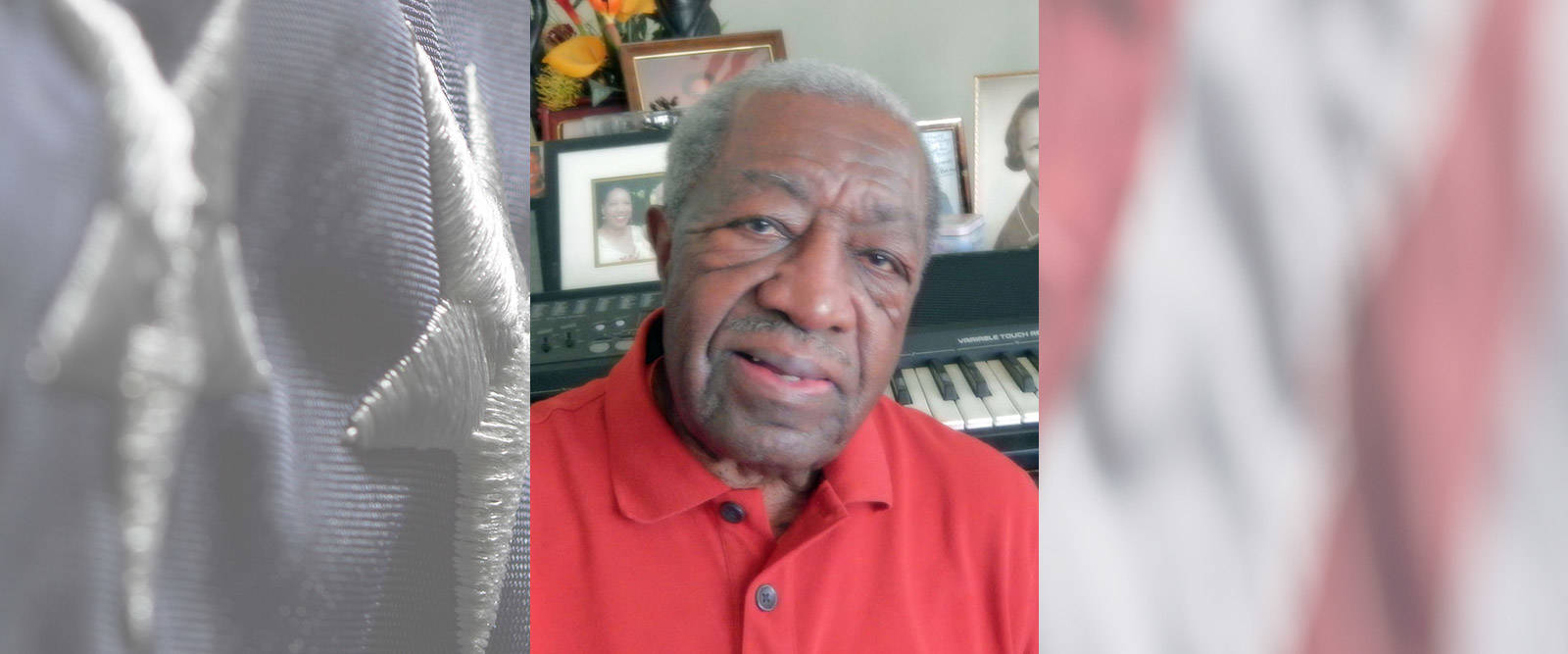

U.S. Army Korean War Chicago, IL Flight date: 05/09/18

By Donna Pacanowski, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Charles A. Griffea was born in a small town near Memphis, Tennessee in 1927. He was the youngest of nine children. At the age of 16, after the death of their mother, he and a brother moved to the Pontiac, Michigan area to live with relatives. After finishing high school, he was hired to work on the assembly line at the Pontiac Automotive Plant. The job was good, wages were decent, and he could have easily remained there for the foreseeable future. However it was 1950, and world events would soon change the life that Charles had into one he could have never imagined.

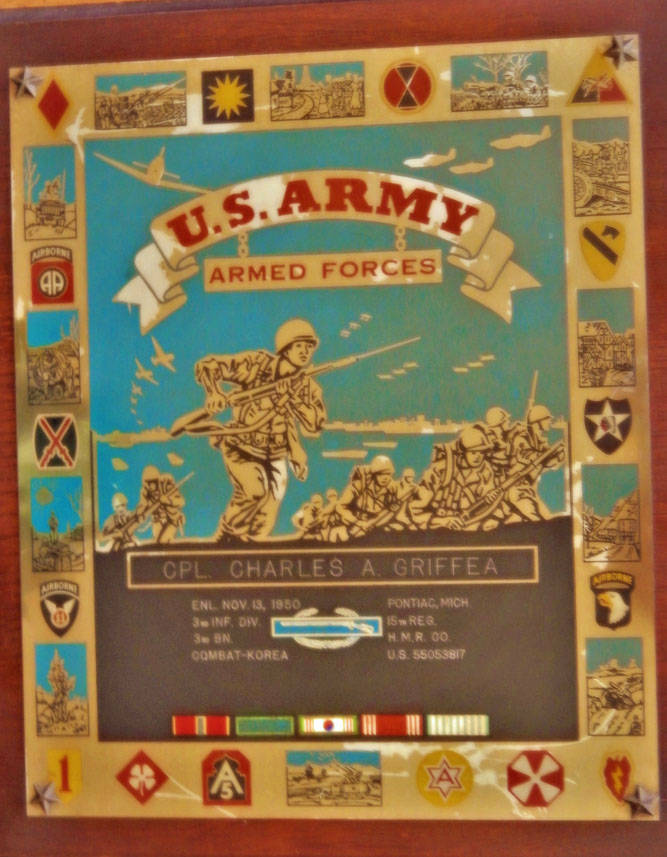

By November 1950, Charles had been drafted into the Army and was on a train bound for Fort Campbell, Kentucky. There, he received weeks of Basic Training and Advanced Infantry Training. By April 1951, his unit was on a train to San Francisco, where they were put on the USS Polk enroute to Japan. It was a long, arduous 18 days at sea. Once in Japan, they were transferred to an LST (Landing Ship Tank) for three more days at sea before landing at Incheon, Korea.

Just prior to the Korean War, President Truman ordered full integration of US Troops [READ MORE ABOUT TRUMAN’S EXECUTIVE ORDER HERE]. Charles and other black personnel from Fort Campbell were assigned to the all white 3rd Infantry Division from Georgia. He and eight others were assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division, 15th Regiment, HMR Company. When asked to describe the circumstances at that time, Charles related that there were a few problems. But with the conditions that they were experiencing in combat, they “were all too busy trying to stay alive” and all worked as a team to defeat their common enemies: the Chinese, the North Koreans and the bitter weather.

They were referred to as reinforcements, but they quickly learned that they were actually replacements, as so many men had been seriously injured or killed. Charles had to quickly learn the basics of mortar operations, when he was assigned to a Heavy Mortar Platoon, manning a 4.2 inch mortar. He described being in combat, “At first, I was scared to death.” But as the constant fighting in his initial weeks of combat continued, Charles realized that he had an important responsibility and fear became secondary.

The North Korean and Chinese attacks were relentless, wave after wave were thrown at the United Nations’ lines. A forward observer told Charles that mortar rounds were “dropping like rain.” The explosions were tearing up men and equipment, but the enemy kept coming. Charles said “the Communist officers would shoot any of their own soldiers if they failed to move forward.” The Chinese and North Korean forces were unconcerned about how many of their own troops died, as long as they could inflict some casualties.

If the dirt roads and mountainous terrain of North Korea weren’t difficult enough for moving men, equipment and supplies in the warm months, when winter set in, they quickly learned that surviving mud, snow, ice and -30 degree temperatures was “the real challenge.” Conditions were brutal. Frostbite was common. Charles showed several of his fingers that had been affected, but as he said, “men are wounded and dying all around you, what’s a little frostbite ?” While he was not wounded, Charles injured his back when moving the base plate of the mortar (over 100 lbs) by himself. He was hospitalized for only two weeks, and rejoined his unit.

During his tour, Charles received the Combat Infantry Badge, the Bronze Star for Valor, the Korean Service Medal, the Korean Unit Citation, and National Service Medals. He was promoted to Corporal. His unit saw action in battles including Pyongyang, Seoul, Incheon, and the Pusan Perimeter and was constantly in motion as the tide of battle shifted.

When asked to describe his military experience, he said that he was proud to have served, and it was ”life changing, for better or worse.” He acquired discipline, confidence, and knowledge that could only come from experiencing that tour of duty. It also, however, showed him the horror and destruction of war that took the lives of many of his comrades.

Charles earned enough points to leave Korea after 11 months, 25 days. With his tour in Korea over, he was put on a troopship back to San Francisco; after processing he was sent by train to Fort Custer in Kalamazoo, Michigan. There, he finished an additional eight months Active Duty requirement and was discharged in 1953. He still, however, would have an additional four years of Army Reserve service to complete.

He returned to Pontiac, Michigan and his former job at the Pontiac plant, but about a year later he moved to Chicago to join his sister. There he held a variety of jobs while continuing his education under the GI Bill at Wilson Jr. College. While working at the Post Office, he met up with one of his comrades from Korea; this renewed a friendship that continued for many years. He later started his own business, Griffea Tax Service, which he operated for over 40 years.

His sister introduced Charles to his future wife. Her friend, Julia, needed help in painting and decorating her apartment. Charles was only too happy to comply. After about five years, Charles and Julia were married. Their marriage lasted over 50 years until her death in 2010. Julia and Charles were blessed with one son, three daughters, five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Charles, we honor you for your sacrifice and bravery during the Korean War. Enjoy your well-deserved trip with Honor Flight Chicago.